| Numinous The Music of Joseph C. Phillips Jr. |

The Numinosum Blog

|

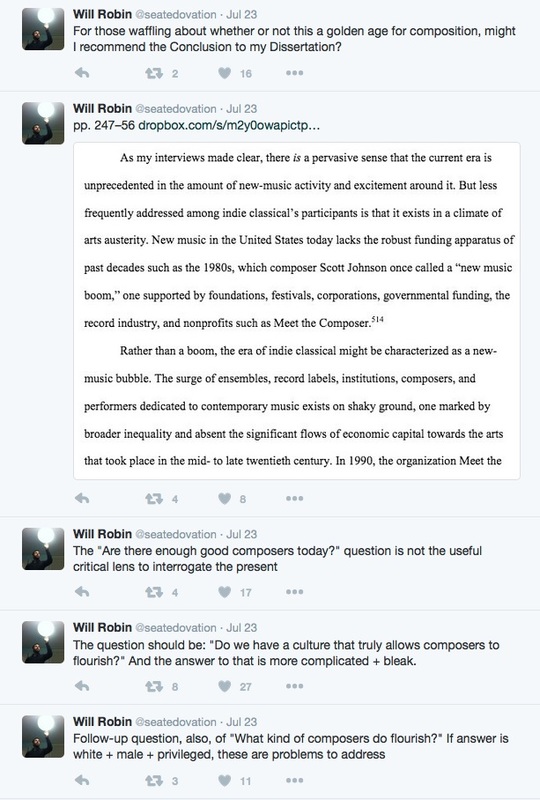

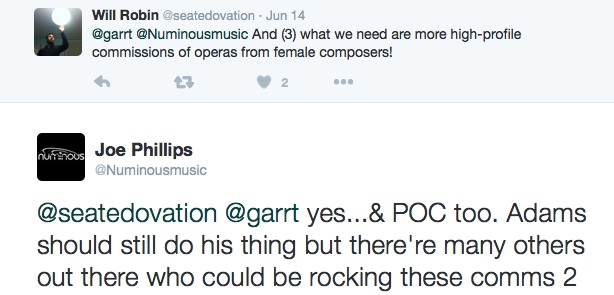

What kind of culture allows composers to flourish and what kind of composers do flourish? These above recent questions on Twitter from musicologist/writer (and now Doctor/Professor) Will Robin are in reference to his doctoral dissertation, A Scene Without A Name: Indie Classical And American New Music In The Twenty-First Century. A wonderful and thoughtful read into the development over the past ten years or so of that music scene centered around New Amsterdam Records, and which I am (somewhat) a part of. As I was reading the dissertation, and before seeing these tweets, I was already pondering Will’s questions of inclusiveness, luck, privilege, and opportunity in the new music/indie classical scene, as well as in the broader classical music industry eco-system. Although not my primary focus, a few of the larger themes about inclusiveness that Will discusses in his dissertation, I hinted at in my Master’s of Music thesis, The Music Composition Miscere, the Historicity of Mixed Music and New Amsterdam Records in the Contemporary New York City Mixed Music Scene (2011); one example, from page 159: The social aspects around the NewAm community reflect a particular early twenty-first century New York City fin-de-siècle: erudite and well-educated, mostly white composers and musicians under the age of forty, whose individual backgrounds, while certainly unique and different, consist of a general similarity of experiences, backgrounds, and socio-economic status. And while all scenes “are, in fact, just quick polaroids of who happens to be in a certain place at a certain time,” can this NewAm boutique community filled with “friends” and people of like minds and similar backgrounds, broaden itself into a substantial movement filled with different kinds of people not like themselves? Going back to Will’s follow-up question, as I was contemplating “what kind of composers DO flourish (emphasis mine)? If it is white + male + privileged, these are problems to address”, composer and Twitter friend Garrett Schumann tweeted, and I replied: Now I think I get what Garrett was intimating—indie classical is to classical as craft beer is to beer—but as I thought more on the issue, maybe he was more right than even he thought. I had read the article, “There are Almost No Black People Brewing Craft Beer. Here’s Why” many months ago but it was the first thing I thought about when I saw Garrett’s tweet last week; and the parallels between the various cultures became apparent when you substitute “(indie) classical/new music” for “beer/craft beer” below: It’s important to note that no one I spoke with for this story claimed or even hinted that the enthusiasm gap between white and black consumer bases was driven by racism. Instead, the takeaway of many of these conversations boiled down to a simple fact: craft beer is white because the overall American beer industry has always been white. With #Oscarsowhite, #Hollywoodsowhite, the recent “whitewashing” controversy of casting in movies Aloha, Gods of Egypt and Ghost in the Shell (of course this has been going on for a long time), the Paul Ryan photo of interns in Congress, and many other examples in contemporary society, one can see that those who mostly have easier access to and more chances at institutional opportunities and resources are the same as they’ve always been: white, privileged, and mostly male. Just as in the accumulation of wealth in white families over generations, often at the expense of others being able to do similar because of systemic inequality and injustice, today’s classical music landscape hides advantages already “baked into the system” for some; and that a few non-whites and females find some notice, is in spite of said system, not an indication of a post-racial or post-gender equalitarianism. Like in the society writ large, for those not already in positions of privilege or advantage, the Horatio Alger myth of working hard, developing an innate talent, doing great work the “right” way, is no guarantee of any kind of opportunity or success or social mobility. While it never has been easy, this new music community with it’s incredible openness and, if you will, a very liberal sensibility (using this here not in a political term, although could certainly also apply in that context to describe many) to varying viewpoints seemed to auger for better (as quoted in the above article about craft beer, but certainly fits in this context—the new music community is “‘one small area where we can make an effort to take a chunk out of racism, rather easily’ because it is a relatively progressive enclave. ‘If we can’t do it here -- when everyone’s feeling good and giving high-fives–then we’re in trouble’”). Unfortunately this “historically unprecedented moment of opportunity as young artists” as Clare Chase stated in her graduation speech at Northwestern University (and Will quotes in the dissertation), is not referring to everyone. In today’s hyper-segmented society with a vast universe of metaphorical background “noise”, how can one establish a signal bright enough that will bring enough attention to allow a sustained and continued musical career, if you are not a white male, under 40 years old? One way is to have benefactors/mentors to help advocate your way forward; when Meryl Streep was just trying to get her way into the door with Kramer vs. Kramer she had some early help that, if wasn’t there, the world could have missed out on the future MERYL F**KING STREEP: Getting Meryl [Streep] past the studio hadn’t been easy. Some of the marketing executives at Columbia thought she wasn’t pretty enough. “They didn’t think that she was a movie star. They thought that she was a character actress,” Richard Fischoff said, describing exactly how Meryl saw herself. But she had her advocates, including Dustin Hoffman and Robert Benton, and that was enough to twist some arms. (Vanity Fair, March 2016) Or this story of film composer Bear McCreary getting his break through a chance meeting, which helped him meet a composing idol: And quite frankly, I think the only reason that a 24-year-old kid with no credits is the composer of Battlestar Galactica is because it was a television show… [Bear] McCreary's career goes back to a chance encounter when he was a junior in high school. The local rotary club in Bellingham, Wash. named him "student of the month," and at the awards luncheon it came up that he was interested in film music. After the event, a man named Joe Coons came up to him and told him he had a friend in the business. And I thought, 'All right, whatever, man,' McCreary recalls. And he says, 'Have you heard of Elmer Bernstein?' And my jaw hits the floor. I mean, this guy had written some of my favorite melodies, ever"….That's how I met Elmer Bernstein. And I ended up working for Elmer for seven to 10 years. Honestly, it’s hard to fathom that a 24-year old black or brown kid with no film or TV credits (and who didn’t have Elmer Bernstein opening doors, or more sadly, even if they did) ever getting to even BE in a position to get that kind of opportunity with a major studio production (hey Marvel, while I have written music for film, I would LOVE to have that “McCreary shot” for the upcoming Black Panther (or Captain Marvel) movies... I'm serious--you know where to find me…). Actually Bear’s story illustrates two points about how composers can get the opportunity to flourish: one, he got to meet an advocate, who while offering advice, also helped open doors; but the second, more salient point was that he had a network that included friends and acquaintances that had access to someone influential and necessary in helping to get the opportunity to even start his trajectory in the first place. In my thesis I quote composer/vocalist Shara Worden (now Nova) from the article “Playing Between Rock and a Classical Place” (Wall Street Journal, Jan. 15, 2011) encapsulating some of the interconnectedness baked into the indie classical scene: The really beautiful thing is that it's really based on friendship. There's a crew of us, and it's a bit incestuous. This quote always bothered me. Now, I understand and actually agree with the basic premise of what she is saying: life’s too short to waste time and energy on crazy so that working with friends, people you know, like, and are comfortable with is joyous and rewarding. But in its effect, it feels a little like “cafeteria tribes”—if you are lucky enough that your tribe includes people who are already “in” (or can more easily GET in) and then can hold the doors open for friends, everything is great. It reminds me of a little like living in New York: if you have lots of money, the city can seem to offer unlimited possibilities and pleasures; if you don’t, it’s a different city of constant struggle and hustle…with few pleasures. Now this illustrates some of the implicit privilege or luck, which is in the DNA of the system for some. This ties directly into answering Will’s question about what kind of composers get to flourish in the current environment (and partly, the how), I believe luck is preparation meeting opportunity. If you hadn’t been prepared when the opportunity came along, you wouldn’t have been ‘lucky.’” Could I ever say with a straight face that luck played no role in my career? Of course not. There are plenty of talented writers out there who don’t have the good fortune to have friends already working in media who will invite them to a party where they may make a connection that will change the rest of their lives. But as I also explained in my interview with Levo League, I work extremely hard. I try always to be prepared so that when an opportunity comes along, I’m ready to make the most out of my lucky break. After getting my book deal, I turned in a finished book in six months while simultaneously finishing a master’s degree at Columbia University. That part, and the positive reviews that followed, had nothing to do with luck. That, as Sklar might say, was all my sweat and ‘giving a damn’ (http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/05/19/i-m-not-ashamed-to-admit-i-got-lucky-and-neither-should-you.html). Of course, having the luck/privilege of going to the “right” school, living in the “right” neighborhood, having the “right” background, financial stability, and friends all goes in to helping some have the opportunity to be in a position to be able to give all your “sweat” and a “damn”, which more likely can lead to early success. But what is success or flourishing as a composer anyway? Commissions from classical music institutions? Putting out well-received recordings? Ability to tour? Making your living off of music? Getting tenure at a university? Having Philip Glass as a mentor? Certainly the answer is different for everyone, but as Will states above, the possibility of achieving whatever one’s definition of success is, is more and more “complicated and bleak” in today’s society, even for the privileged. Success/flourish is obviously often not one or two points but a continuum, a cloud if you will, that is built upon by various steps over time; the accumulation of the “right” elements, which are different for different people—family and musical background & experiences, temperament, talent, social network circumstances & opportunities, and just plain luck—that builds upon itself (the cloud metaphor is appropriate here: not only in how clouds form, but also as seen from afar—they look formful & defined, but upon closer inspection you realize that where it begins is often undefined and diffused but once you are fully in it, you know). Like how people talk about the achievement gap, if you don’t start off with the opportunity to accumulate those first steps in development then you are always playing “catch up” and you’ll face stiffer and deeper difficulty than if you had the plow cleared for you early on (and this doesn’t mean one CAN’T make headway to overcome the deficiencies, just means more struggle to achieve). So reading Will’s dissertation I remarked at the “general similarity of experiences, backgrounds, and socio-economic status” of the people written about (young-ish, white, mostly male, middle/upper middle class, Ivy League educated), and, while the ones I know personally are some of the hardest working people I’ve met, they nonetheless have benefited because of “the academic settings, institutional ties, and privileged backgrounds that have allowed this generation to flourish, the rhetoric of ‘honesty’ and ‘naturalness’ in ‘music without walls’ runs the risk of misleadingly valorizing entrepreneurship. As Andrea Moore has documented, the promotion of arts entrepreneurship is increasingly common among music schools in the United States. When careers of such ‘self starters’ as [Nico] Muhly, [Judd] Greenstein, and [Missy] Mazzoli are used as models for such programs—without necessarily telling the ‘full story’ of their musical backgrounds—it can perpetuate false narratives of replicable success (Robin, pages 260-61).” I often think about those many others not in the scene—those not already in resonance with critics whose “personal histories… are drawn to something that they were each already, in a way, looking for” (Robin, page 96); those “…African American experimental musicians…often ignored or critiqued by writers who subsequently lionized the comparable boundary crossing of white artists…” (Robin, footnote #34); those black artists that “channel R&B, funk, and hip-hop, while their white contemporaries get kudos for giving makeovers to the likes of Radiohead, Nick Drake, and Bjork” (Interview with John Murph on Open Sky Jazz “Ain’t But a Few of Us: Black jazz writers tell their story Part 2”; those composers discussing and building their own wonderful scene of community and support on #Musochat—that given similar chances (and frankly luck/fortune) could create and develop into similar levels of success and acclaim but find it increasingly more difficult with the decks more stacked against, and “the mechanisms that allowed indie classical to gain prestige and institutional support have been disrupted. Future cohorts of composers will continue to emerge, but is not clear how they will transform cultural capital into economic capital to create the kind of sustainable careers that New Amsterdam has sought for its artists. The rhetorical positioning of indie classical—that it came into existence outside the ‘strictures’ of the concert hall and the academy—may create the false impression that the next generation could thrive without the traditional infrastructure of classical and new music.” (Robin, pages 260-61). The path(s) taken by those younger composers in the dissertation, which itself was/were originally blazed by those composers in the 60s and 70s, to take advantage of Claire Chase’s “historically unprecedented moment” is/are harder and harder to see for more and more composers now, but especially composers of color. Many years ago I used to substitute teach in NYC public schools. I went to schools all over the city—anywhere from the Upper West Side in Manhattan and Park Slope in Brooklyn to East Harlem—and was always shocked by the disparity between the amount of resources available to those schools in wealthy neighborhoods compared to those in less affluent areas. Now in every school and neighborhood there were smart, inquisitive students (and also those less so); but always with the less wealthy schools, I would lament for those talented, smart black and brown faces I saw (because that’s usually the only faces I did see in those schools) because I just wished that those kids could have had the chance to be in a school environment with the same resources, to have similar life experiences that I found with the students in the richer areas. Of course I did not wish those kids in the wealthier districts didn’t have what they had, I just wanted something similar for all those other talented kids in the other districts, who I KNEW would benefit from the same opportunities those Upper West & East Side/Park Slope/Carroll Gardens/Brooklyn Heights kids had—a good chance to fulfill their full potential; I SAW and FELT the gaping disparity and but for the factor of circumstances they didn’t control, those kids COULD have had but didn’t. And reading the dissertation, while happy for how some composers were able to rise above to be heard and noticed, I also felt that same pang for all of those other composers out there that would not get the same chances. How can it change? Well one way, short of having more POC and women in boardrooms making programming decisions or others on the "inside" the club to look "outside", maybe there needs to be some kind of indie classical/new music “Rooney rule”. While not perfect, the Rooney rule has helped people of color in the NFL to be considered to high level positions. So next time a symphony or institution relies on the bromides about how they can’t ‘find’ women or black/brown composers or when they say, “Hey what about [any-number-of-names-we’ve-heard-before-and-who-will-be-fine-if-they-don’t-get-that-commission/award-from-your-esteemed-organization] for that commission maybe the Rooney rule could be there to say, ‘you know, there are other great composers out there that aren’t friends/acquaintances/people someone went to school with/in our usual circle, let’s find out more about them.’ Hey, as I said in a tweet: Black and brown composers don't want to be tokens or diversity experiments but, like any composer, just want the same opportunity to “get in the room…to have a real chance..." as anyone else; and, we'll take it from there.

You can now hear our March 16th, 2013 Ecstatic Music Festival performance with Imani Uzuri on WQXR's Q2.

POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 1:09 PM  Numinous @ Ecstatic Music Festival 3.16.13 photo by David Andrako Numinous @ Ecstatic Music Festival 3.16.13 photo by David Andrako Tomorrow the Ecstatic adventure continues!: Moderated by Ecstatic Music Festival curator Judd Greenstein I'll be discussing my composition Changing Same, my Festival collaboration with Imani Uzuri, as well as other musical sundries on Wednesday March 20th at 6pm at the Merkin Concert Hall upper lobby. Attendance at the talk is FREE and various libations and eats will be available for purchase. This event takes place just before the penultimate 2013 Ecstatic Music Festival concert with Steven Mackey, Rinde Eckert, Big Farm, and JACK Quartet and if you don't have tickets for what promises to be an outstanding show, you can purchase at Merkin. I'm going to the concert after the talk, so hopefully I'll see you at both! POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 4:57 PM An incredible night of music last Saturday March 16th as myself, Numinous, & Imani Uzuri took the stage of Merkin Concert Hall in NYC for our performance at the Ecstatic Music Festival. It truly was a magical experience with the enthusiastic audience showing us love for the premieres of my composition Changing Same, Imani's Placeless, and our joint piece Awe & Humility. Luckily it was recorded and will soon be available to listen on WQXR's Q2, but for now you can check out Facebook for some of the great official photos taken by David Andrako (you don't have to be on FB to view). Also be sure to check out David's website where you can see some of his other amazing photos including from previous Ecstatic Music Festival concerts).

Thanks to all of the musicians, the Festival, curator Judd Greenstein, Merkin Concert Hall, Kaufman Center, all those in attendance, and of course to Imani Uzuri for the wonderful experience. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 9:54 PM This post is the sixth in a series profiling some of the inspirations and thoughts behind the six movements of my composition Changing Same premiering March 16th, 2013 at the Ecstatic Music Festival in New York City. Previous posts in the series featured:

6. “Unlimited” “…we cannot solve the challenges of our time unless we solve them together – unless we perfect our union by understanding that we may have different stories, but we hold common hopes; that we may not look the same and we may not have come from the same place, but we all want to move in the same direction – towards a better future for our children and our grandchildren.” 1  In January 2009 I stood freezing on the National Mall in Washington D.C. with two million others witnessing Barack Obama become President of the United States. Standing there with faces black, brown, and beige there was a palpable sense of excitement and anticipation that the truly unlimited opportunity the original “promise of America” represented, seemed finally reachable to not only someone like me, but seemly anyone and everyone with ability, a dream, temerity, perseverance, and luck. That day felt like a beginning, where the phrase “one nation” took on renewed resonance and meaning. And while the realities of governance since then have tempered the fires of hope, they have not extinguished them. No matter her ultimate direction America is forever changed, not only for the now but for the “unborn millions to come” in the long now. Producers Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff with their “Philly Sound”—an often energetic and richly orchestrated dance music—are sometimes credited with laying the foundations for disco in the 1970s. In my ancient early days growing up, before I had any idea of who Gamble and Huff were or exactly what disco was, the songs they produced—such as “Me and Mrs. Jones,” “Back Stabbers,” “Now that We Found Love,” “Love Train,” “For the Love of Money,” “When Will I See You Again,” and “TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia)” (also known as the Soul Train theme song)—formed an indelible imprint on an impressionable little kid. Often I was less interested about what the singers actually sang about (was too young to understand much anyway). Rather, I enjoyed the mood, atmosphere, and energy those songs created; the sophisticated way they moved you or made you want to move, “it like put a bow tie on the funk. It made it elegant." 2 Echoes from “The Love I Lost” by Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes featuring the incredible lead singing of Teddy Pendergrass and “Love’s Theme” by Barry White’s Love Unlimited Orchestra (an artist influenced by Gamble and Huff) can be heard throughout “Unlimited.”

(note: the YouTube video of the 1994 documentary Rock & Roll is from the BBC version, and NOT the version that aired on PBS and that I recorded on my VCR back then; among some slight, but noticeable differences between the two versions are the PBS version was narrated by Liev Schreiber and also featured some different musical acts shown. The opening part on the above video clip features the song "The Love I Lost" and is in both versions) Notes 1. From Barack Obama’s “Speech on Race” in Philadelphia, March 18, 2008. (Transcript, New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/18/us/politics/18text-obama.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0). 2. Quote from Fred Wesley, trombonist in James Brown Band. From "Making it Funky" episode of PBS/BBC documentary by David Espar Rock & Roll (1995). POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 10:00 AM This post is the fifth in a series profiling some of the inspirations and thoughts behind the six movements of my composition Changing Same premiering March 16th, 2013 at the Ecstatic Music Festival in New York City. Previous posts in the series featured:

5. “Alpha Man” "You really want to know what being an X-Man feels like? Just be a smart bookish boy of color in a contemporary U.S. ghetto. Mamma mia! Like having bat wings or a pair of tentacles growing out of your chest. "1 I did not grow up in a ghetto, but that sentiment most definitely fit me in my younger years. Glasses, check; Comic books, check; computers, check. And while I was an outstanding athlete growing up, and had that to fall back on in the neighborhood social hierarchy, one of my younger pursuits was drawing my own comic books. One character I created was called Alpha Man: a lowly Earth physician who through a freakish accident (naturally) was imbued with the ‘cosmic force.’ Initially he was (ambivalently) on a team of evil, but after a nasty defeat he was banished to the far reaches of the galaxy, where he became a solitary exile wandering the universe; in the process he became a wise and sage protector. While one can detect hints of the Silver Surfer, the character of Alpha Man was more influenced by Carl Sagan. In his groundbreaking television series, Cosmos, which I watched as it premiered on PBS, a number of episodes imagined an interstellar space-ship, piloted by a single life form, traveling the mysteries of the universe collecting information for an ‘Encyclopædia Galactica’. This image continues to hold a particular fascination for me. Profane, beautiful, ebullient, and melancholy, it speaks of the eternal; not only of the infinity of the universe itself, but also the infinite capacity and imagination of the mind to explore the unknown (and the unknowable). About ninth grade Gustav Holst’s The Planets was the first cassette tape I remember asking my mom to buy me. The entire piece, which sounded little like anything I had ever heard to that point (well maybe John Williams’s Star Wars), had a deep impact on my beginning musical aspirations. The movements “Venus” and “Saturn” were not my favorites back then (“Mars” and “Jupiter” were) but since then have offered inspiration that found its way into “Alpha Man.” “Saturn” from Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life, an album that was a tutor in my early musical schooling, was another appropriate addition to the development of “Alpha Man.” Ecstatic Music Festival with Imani Uzuri Saturday March 16th, 2013 7:30 pm Merkin Concert Hall 129 W. 67th Street (between Broadway and Amsterdam Ave) NYC Check back as I'll post some more crib notes about the movements from Changing Same. Notes 1. Junot Díaz, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, 22 (Riverhead Trade, 2008). POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 9:30 AM This post is the fourth in a series profiling some of the inspirations and thoughts behind the six movements of my composition Changing Same premiering March 16th, 2013 at the Ecstatic Music Festival in New York City. Previous posts in the series featured:

4. “The Most Beautiful Magic” I don't remember the first time I heard something from Prince and the Revolution's Purple Rain, but I definitely remember friends coming back to school raving about the tour in 1984 and it's sold-out two-week legendary run at my local arena (regretfully I didn't go and it would be another 10 years or so before I saw Prince live for the first time). Back in the day, before he started being more accessible to interviews and public appearances Prince was this decidedly enigmatic yet strangely compelling figure in my consciousness. Shortly after the album came out I was sitting in my cousin's room one day and listening to the LP (remember the time when one would actually stop the world spinning to sit down and spend time listening); now I'm sure it wasn't the first time I heard songs from the album, since almost everything was on rotation on the radio, but it was the most memorable: reading the LP liner notes, debating who was better, Michael Jackson or Prince, and constantly spinning the record backwards when it got to the end of "Purple Rain" and "Darling Nikki" trying to decode the messages from the ether. It would be another few years before I actually saw the movie, adding another layer of mystery behind Prince and the album. Looking back, this seminal 1984 album was a major influence on my personal musical development. As a young teenager listening to the then just released Purple Rain was revelatory. With its virtuosic and vertiginous mixture of rock, funk, R&B, pop, and electronica, Prince’s “Minneapolis sound” was a perspicacious vision of music as an integrated fusion of styles and genres that wholly resonated with my own nascent mixed music aesthetics, philosophies, and aspirations. “Purple Rain,” “Beautiful Ones,” and “Computer Blue,” three songs from Purple Rain, are the deep structures that help build “The Most Beautiful Magic,” with the emotional inspiration coming from Richard and Mildred Loving. The Lovings were the couple at the center of the landmark June 12, 1967 Supreme Court decision, Loving v. Virginia, effectively ending America’s miscegenation laws banning interracial marriages. “The Most Beautiful Magic” title is a quote from the movie, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince where one character describes the singular beauty that comes from a basic and simple (magical) act. This seemed appropriate to describe the affirmative power and courage of the Lovings to marry despite unjust laws legally denying them the opportunity to do so. As Mildred Loving explained in a speech celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision, their act of defiance “wasn't to make a political statement or start a fight. We were in love, and we wanted to be married.”1 "The Most Beautiful Magic" is dedicated to my wife. Notes 1. This statement from Mildred Loving was prepared for the 40th anniversary of the Loving v. Virginia Supreme Court decision. See http://www.freedomtomarry.org/pdfs/mildred_loving-statement.pdf. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 10:00 AM This post is the third in a series profiling some of the inspirations and thoughts behind the movements of my composition Changing Samepremiering March 16th, 2013 at the Ecstatic Music Festival in New York City. The other parts of the series included:

I remember hearing and reading the buzz about mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson's much-heralded 2003 Nonesuch recording of J.S. Bach's cantata Ich habe genug BWV 82 long before I was actually able to hear it (knowledge of the powerful Peter Sellars staging of the two Bach cantatas featured on the album came later still; and I must say I was not disappointed when my ears finally were able to hear Lieberson's exquisite voice on the recording). I first heard the song "Someday We'll All Be Free" when Aretha Franklin's version was featured in the 1992 film Malcolm X(an aside: if Daniel Day-Lewis was rightly lauded by the Oscars for his impressive channeling of the "Great Emancipator" in Lincoln, then Denzel Washington's equally compelling Malcolm, should have been also justly swaged by the Academy). It wasn't until almost a decade after seeing Spike Lee's film that I found my way to Donny Hathaway's original 1973 version on his last studio album, Extensions of a Man. Both the Lieberson version of Ich habe genug and the Hathaway version of "Someday We'll All Be Free" are the musical inspirations behind my "Miserere." Traditionally Miserere is a musical setting of the 51st Psalm (Miserere mei, Deus, secundum misericordiam tuam ("O God, have mercy upon me, according to thine heartfelt mercifulness") and has been set by composers such as Gregorio Allegri, Josquin des Pres, Henryk Gorecki, and Arvo Pärt. My “Miserere” however does not seek to reflect any kind of religious faith of salvation in the hereafter; rather it is a lamentation of more terrestrial pleadings. Taking inspiration from the Bach, whose title translates to “I have enough,” the original lyrics of “Miserere” begin with "I have had enough" and continue expressing weary frustration and doubt in the ability to come to terms with one’s many struggles and problems. The lyrics of “Miserere” convey a muted sense of earthly hope in the face of a seemingly increased hopelessness. And perhaps it is that hope in the face of hopelessness and doubt, one will "emerge from all the suffering that still binds [us] to the world."1

Ecstatic Music Festival with Imani Uzuri Saturday March 16th, 2013 7:30 pm Merkin Concert Hall 129 W. 67th Street (between Broadway and Amsterdam Ave) NYC Check back as I'll post some more crib notes about the movements from Changing Same. NOTES: 1. “Da entkomm ich aller Not, Die mich noch auf der Welt gebunden.” J.S. Bach, Ich habe genug, translated by Pamela Dellal,http://www.emmanuelmusic.org/notes_translations/translations_cantata/t_bwv082.htm POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 7:56 PM This post is the second in a series profiling some of the inspirations and thoughts behind the movements of my composition Changing Same premiering March 16th, 2013 at the Ecstatic Music Festival in New York City. 2. “Behold the Only Thing Greater than Yourself” I remember sitting down as a family to watch the mini-series Roots and ours were one of many families that did the same. Roots became a talked about topic in my neighborhood and in the backyard football and baseball field. Not that I was particularly interested in slavery but even the young elementary school kid I was recognized that Roots was an amazing achievement at that time: an entire high-profile TV series based on black characters that not only black people were interested in watching. It taught a very early lesson to me that stories involving black people and lives were also worth watching and telling. The title for the second movement of Changing Same comes from the scene in Roots when the family patriarch lifts his newborn child to the star-filled night sky and proclaims “Behold, the only thing greater than yourself.” Those words are a powerfully plangent call valuing one’s intrinsic self-worth and potential in spite of societal resistance often working in opposition to maintaining a positive self-evaluation. Throughout America’s history, blacks confronted this resistance, as James Baldwin wrote, by “groaning and moaning, watching, calculating, clowning, surviving, and outwitting” with “some tremendous strength…nevertheless being forged, which is part of [black] legacy today.”1 And today it is often single mothers left to hold on to that legacy, presenting their children before the world with the gift of love, resiliency, resolve, and strength. This movement is dedicated to my mom, who struggled as a single parent to raise me and my siblings with that gift of love and strength, resolve, and resiliency so that we are able to not only survive but live and thrive; to have skills and fortitude to take advantage of any opportunity, adding a small contribution to that legacy. Ecstatic Music Festival with Imani Uzuri Saturday March 16th, 2013 7:30 pm Merkin Concert Hall 129 W. 67th Street (between Broadway and Amsterdam Ave) NYC Check back as I'll post some more crib notes about the movements from Changing Same. NOTES: 1. James Baldwin, “An Open Letter to My Sister, Miss Angela Davis.” POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 10:00 AM This post is a first in a series profiling some of the inspirations and thoughts behind the six movements of my composition Changing Same premiering March 16th, 2013 at the Ecstatic Music Festival in New York City. 1. “19” “[W]e must fight for your life as though it were our own—which it is—and render impassable with our bodies the corridor to the gas chamber. For, if they take you in the morning, they will be coming for us that night.”1 Being a very young kid growing up in the 1970s I was still forming my thoughts about life. But some images from the media stuck out and left an indelible impression on me about the range and diversity in the black world: movies such as Car Wash and The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings and other blaxploitation films (although I didn't know the term then), TV shows such as Soul Train, Good Times, Sanford and Sons, Fat Albert and The Jeffersons, Dr. J, Mohammed Ali, Sugar Ray Leonard, the great multi-ethnic Big Red Machine, the Parliament Funkadelic LPs of my parents, and the black cultural movement featuring powerful political figures such as Shirley Chisholm, Harold Washington, and Angela Davis. Even though I was too young to understand exactly who or what she was or about, the image of a full Afro'd Angela Davis speaking was quite iconic to my young mind. “19” is partly inspired by a number of seemly disparate musical sources: Arnold Schoenberg's Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke opus 19 from 1911 (one of the first Schoenberg pieces I studied and liked, specifically the Maurizio Pollini DG recording--nineteen is also the age when I began studying music as an undergraduate, after two years working toward a biochem major), Curtis Mayfield’s “Little Child Runnin’ Wild” from his seminal score to the 1972 film Superfly, and a hint of the go-go music of Chuck Brown. The emotional timbre of “19” however, is inspired by the activist Angela Davis and her status in the black culture of my youth. Writer James Baldwin's November 19, 1970 “An Open Letter to My Sister, Miss Angela Davis” is stirring in its description of Davis as a soldier in the on-going struggle for racial and social equality and a martyr in the “enormous revolution in black consciousness…[that] means the beginning or the end of America.”2 The letter, while condemning the false arrest of Angela Davis that summer, goes on to describe the contemporary state of racial dynamics in the United States in biting and incisive commentary. Ecstatic Music Festival with Imani Uzuri Saturday March 16th, 2013 7:30 pm Merkin Concert Hall 129 W. 67th Street (between Broadway and Amsterdam Ave) NYC Check back as I'll post some more crib notes about the movements from Changing Same. NOTES: 1. James Baldwin, “An Open Letter to My Sister, Miss Angela Davis.” 2. Ibid. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 11:30 AM MONDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2013

"R&B is about emotion, issues purely out of emotion. New Black Music is also about emotion, but from a different place, and finally, towards a different end. What these musicians feel is a more complete existence. That is, the digging of everything." -LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), “The Changing Same” (1966) Changing Same, my composition premiering on the Ecstatic Music Festival on March 16, 2013, is a philosophical and musical departure for me: it is a conscious acknowledgement of my early heritage in black popular music and culture. Previously my work was little interested in specifically or overtly reflecting this background in my musical language; my philosophy was (and still is) representative of a ‘post-black’ artistic freedom to explore any creative interest, unburdened with the obligation of only representing or being influenced by ‘the race.’ I am a composer, not just a ‘black’ composer. My journey ‘home’ began a few years ago when I was taken aback by something writer John Murph stated in an interview: “…there’s the whole idea of what is deemed more artistically valid… [with] artists incorporating contemporary pop music. I notice a certain disdain when some black…artists channel R&B, funk, and hip-hop, while their white contemporaries get kudos for giving makeovers to the likes of Radiohead, Nick Drake, and Bjork.”1 While my influences growing up (and now) are quite catholic—an inter-cultural fluency wherein James Brown and Yes, Eddie Van Halen and John Coltrane, go-go music and minimalism provide equal inspiration—I wondered if John Murph’s statement was really true and if so, why was it true? Regardless of the validity of the charge, this question provoked a challenge in me. Fueling a desire, like Duke Ellington in the 1940s with Black, Brown, and Beige or Wadada Leo Smith recently with Ten Freedom Summers, to create music that speaks to the “dichotomies of high and low, inside and outside, tradition and innovation”2 within black culture and explores the richness and complexity of being black in 21st century America; but also music that resonates a more universal artistic expression filtered through the changing sameness of an intimately autobiographical perspective. So-called indie classical/alt-classical is a reflection of alternative rock and other vernacular music as a palimpsest for the creation of new contemporary music of an expansive and open definition and vision. I wanted to express similar aesthetic ideas however using black vernacular music as the main source, testing John Murph’s assertion. From these musings the gestation of Changing Same began. Musically almost every movement is influenced by a fragment, motive, or chord progression from various black popular music influences I grew up with. I, however, wanted to recognize other sources of inspiration as well—a “digging of everything”—so almost all the movements are connected to various influential classical music and/or personal and cultural memories during my lifetime. This miscegenation is done not in a post-modern sense of ironic collage, but rather as a genuine search to create an organic fusion of artistic and cultural influences, to create a new personal artistic statement that is more than the sum of its parts. This is mixed music. Check back because in later posts I will be discussing the inspirations behind each movement for Changing Same and for the music nerds out there with a few movements I'll provide some detailed analysis. Hope you to see you in March. Ecstatic Music Festival with Imani Uzuri Saturday March 16th, 2013 7:30 pm Merkin Concert Hall 129 W. 67th Street (between Broadway and Amsterdam Ave) NYC NOTES: 1. Interview with John Murph on Open Sky Jazz “Ain’t But a Few of Us: Black jazz writers tell their story pt2,” http://www.openskyjazz.com/2009/06/aint-but-a-few-of-us-black-jazz-writers-tell-their-story-pt2/. 2. Touré, Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness?: What it Means to Be Black Now, 32 (Atria Books, 2011). POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 10:30 AM

Numinous will perform at the Ecstatic Music Festival in NYC. In its third year, this two month festival is one of the premier forums for new music in New York, featuring artists who organically blend different genres and different influences; the Festival "bring[s] artists together for unexpected and often surprising collaborations exploring the fertile terrain between classical and popular music." Numinous is honored to not only be apart of the Festival with all of the other dynamic and outstanding artists, but also with the opportunity to collaborate with an incredible singer and musician, Imani Uzuri.

At Ecstatic we will premiere my new composition, Changing Same, which will premiere on the first half of the Festival performance (and will be recorded soon after). This piece is "bringing it all back home" so to speak: a six-movement composition where some of the early (pre-rock) popular musical influences I had growing up--Prince, Stevie Wonder, Curtis Mayfield, Chuck Brown, Barry White, and Gamble and Huff--directly and subtly inform my contemporary classical musical language to create a compelling, intimate, and affirming musical "memory book." The second half of the concert will feature a composition by Imani, as well as a collaborative composition between myself and Imani. It's going to something special so if you're in NYC in March, get your tickets now!

Check back, in the coming weeks as I publish some details and inspirations behind each movement of Changing Same as well as the other music on the Festival. Saturday March 16th, 2013 Merkin Concert Hall 129 W. 67th St. (between Broadway and Amsterdam Ave) NYC Tickets available for our concert here or get a Festival pass or build your own ticket package and check out some of the other great concerts on Ecstatic (beyond our concert I'll be at a number of the other Ecstatic Music Festival gigs too so maybe I'll see you there as well)! POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 11:00 AM THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 1, 2012

While luckily we've made it through Hurricane Sandy fine, New Amsterdam Records didn't. NewAm, for whom some of you know I'll be going into the studio to record a new Numinous album in 2013, is one of the bright lights of new music in NYC and features a number of friends as well as professional colleagues I respect immensely, so if you can help, even a little, it would be most appreciated. Go to New Amsterdam Presents to read about the damage and how you can help by making a donation. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 5:39 PM  Monday night September 12th, I attended the CD release concert of cellist and vocalist Jody Redhage's newly released recording of minutiae and memory (New Amsterdam Records NWAM031) at DROM on Avenue A on the Lower East Side. Jody is a "cello emeritus" with Numinous, having been in a number of performances over the years as well as on the Vipassana recording. Her emeritus status comes as she has been increasingly in demand and out of town, for example, playing with Grammy-winner Esperanza Spalding on her world tour. But I digress, so seeing how back in 2008 I was at Jody's All Summer in a Day CD release concert at the old Galapagos Art Space, I believe (which happened to be one of the first release and public shows of New Amsterdam Records), it seemed fitting to hear how Jody's stirring mix of cello and voice has developed since that earlier recording. The night opened, not with Jody, but with Corey Dargel and Cornelius Dufallo and a set of art pop songs for voice and violin. If you don't know Corey's music, you probably should check out this feature in the New York Times earlier this year. Going in, I was a bit skeptical about how intriguing voice and violin really could be. But with Cornelius doing a great job of electronically looping various motifs/riffs and then subsequently playing other figures over them/with them, as well as Corey's always compelling and droll words and vocal delivery, I felt the instrumentation complemented the compositions wonderfully and provided a smooth transition into Jody's solo set. Just after intermission, as Jody was setting up music on her stand, the house music died out and clearly something quite different started to play over the PA. The audience did get quieter, although I think everyone was trying to figure what was going on. Some were kind of listening and others continued with their intermission activities. Once the piece was over however, Jody mentioned that it was Anna Clyne's "paint box" from of minutiae and memory that was played as a sort of prequel to the live performance. Jody proceeded to perform all the compositions from the new recording although not in album order. All of the pieces fit in a more somber, contemplative emotional zone and I could clearly see how some kind of visuals or lighting design coupled with the compositions would make for an even more powerful performance experience (maybe something similar to Maya Beiser's World to Come). As it was, I enjoyed most of the music and Jody's playing was passionate, heartfelt, and well-done. As she mentioned at the end of the show, all of the pieces on the new album spoke to her strongly and that love came through beautifully in her playing and singing. Some compositions featured Jody's signature (singing while playing the cello) and a few pieces were just for cello alone or cello with electronic backing tracks. At the halfway mark of the concert I thought my favorite piece was going to end up being Missy Mazzoli's "A Thousand Tongues." I'm a fan of Missy's work (her group Victorie's album Cathedral City is one I get continual listening pleasure from) and love how she subtly mixes electronic textures in acoustic environments in many of her compositions and this piece was no exception. This quote from composer Sarah Kirkland Snider sums up what I like about Missy's work in general and "A Thousand Tongues" specifically: [Missy's music] inhabits a weird emotional space that's dark and anxious…. there are so many odd notes and clashing chords…. there isn't a lot of traditional goal-directed motion, but rather this feeling of a pot forever on the boil — yet you're left feeling like you've gone somewhere. While I enjoyed "A Thousand Tongues" thoroughly, it was a later piece, "Static Line" by Wil Smith, that ended as my favorite of the night. From an opening with drone-like sliding figures that evoked a similar sonic world of Michael Harrison's just intonation drones to a later motivic sensibility that vaguely reminded me of South Indian classical vocal writing to a beautifully elegiac melodic build-up toward the end, I was completely engaged in "Static Line" and look forward to exploring it, as well as all the other compositions, in more depth on the actual recording. (photo credit: Joseph C. Phillips Jr.) POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 8:00 AM |

The NuminosumTo all things that create a sense of wonder and beauty that inspires and enlightens. Categories

All

|

Thanks and credit to all the original photos on this website to: David Andrako, Concrete Temple Theatre, Marcy Begian, Mark Elzey, Ed Lefkowicz, Donald Martinez, Kimberly McCollum, Geoff Ogle, Joseph C. Phillips Jr., Daniel Wolf-courtesy of Roulette, Andrew Robertson, Viscena Photography, Jennifer Kang, Carolyn Wolf, Mark Elzey, Karen Wise, Numinosito. The Numinous Changing Same album design artwork by DM Stith. The Numinous The Grey Land album design and artwork by Brock Lefferts. Contact for photo credit and information on specific images.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed