| Numinous The Music of Joseph C. Phillips Jr. |

The Numinosum Blog

|

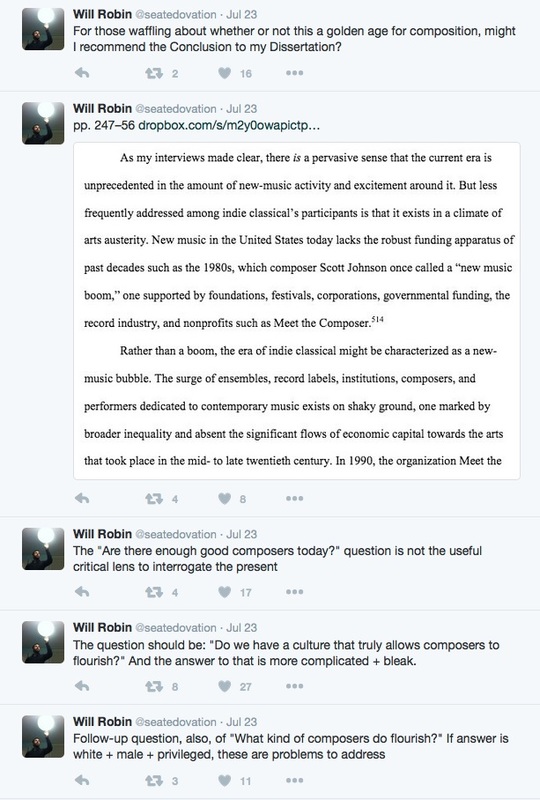

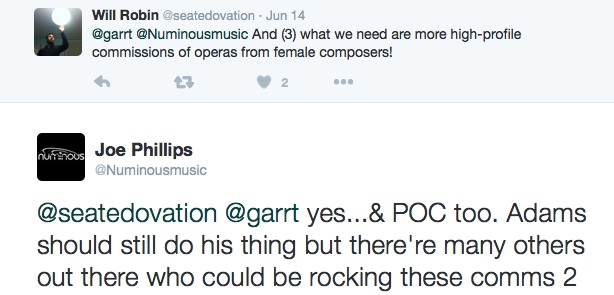

What kind of culture allows composers to flourish and what kind of composers do flourish? These above recent questions on Twitter from musicologist/writer (and now Doctor/Professor) Will Robin are in reference to his doctoral dissertation, A Scene Without A Name: Indie Classical And American New Music In The Twenty-First Century. A wonderful and thoughtful read into the development over the past ten years or so of that music scene centered around New Amsterdam Records, and which I am (somewhat) a part of. As I was reading the dissertation, and before seeing these tweets, I was already pondering Will’s questions of inclusiveness, luck, privilege, and opportunity in the new music/indie classical scene, as well as in the broader classical music industry eco-system. Although not my primary focus, a few of the larger themes about inclusiveness that Will discusses in his dissertation, I hinted at in my Master’s of Music thesis, The Music Composition Miscere, the Historicity of Mixed Music and New Amsterdam Records in the Contemporary New York City Mixed Music Scene (2011); one example, from page 159: The social aspects around the NewAm community reflect a particular early twenty-first century New York City fin-de-siècle: erudite and well-educated, mostly white composers and musicians under the age of forty, whose individual backgrounds, while certainly unique and different, consist of a general similarity of experiences, backgrounds, and socio-economic status. And while all scenes “are, in fact, just quick polaroids of who happens to be in a certain place at a certain time,” can this NewAm boutique community filled with “friends” and people of like minds and similar backgrounds, broaden itself into a substantial movement filled with different kinds of people not like themselves? Going back to Will’s follow-up question, as I was contemplating “what kind of composers DO flourish (emphasis mine)? If it is white + male + privileged, these are problems to address”, composer and Twitter friend Garrett Schumann tweeted, and I replied: Now I think I get what Garrett was intimating—indie classical is to classical as craft beer is to beer—but as I thought more on the issue, maybe he was more right than even he thought. I had read the article, “There are Almost No Black People Brewing Craft Beer. Here’s Why” many months ago but it was the first thing I thought about when I saw Garrett’s tweet last week; and the parallels between the various cultures became apparent when you substitute “(indie) classical/new music” for “beer/craft beer” below: It’s important to note that no one I spoke with for this story claimed or even hinted that the enthusiasm gap between white and black consumer bases was driven by racism. Instead, the takeaway of many of these conversations boiled down to a simple fact: craft beer is white because the overall American beer industry has always been white. With #Oscarsowhite, #Hollywoodsowhite, the recent “whitewashing” controversy of casting in movies Aloha, Gods of Egypt and Ghost in the Shell (of course this has been going on for a long time), the Paul Ryan photo of interns in Congress, and many other examples in contemporary society, one can see that those who mostly have easier access to and more chances at institutional opportunities and resources are the same as they’ve always been: white, privileged, and mostly male. Just as in the accumulation of wealth in white families over generations, often at the expense of others being able to do similar because of systemic inequality and injustice, today’s classical music landscape hides advantages already “baked into the system” for some; and that a few non-whites and females find some notice, is in spite of said system, not an indication of a post-racial or post-gender equalitarianism. Like in the society writ large, for those not already in positions of privilege or advantage, the Horatio Alger myth of working hard, developing an innate talent, doing great work the “right” way, is no guarantee of any kind of opportunity or success or social mobility. While it never has been easy, this new music community with it’s incredible openness and, if you will, a very liberal sensibility (using this here not in a political term, although could certainly also apply in that context to describe many) to varying viewpoints seemed to auger for better (as quoted in the above article about craft beer, but certainly fits in this context—the new music community is “‘one small area where we can make an effort to take a chunk out of racism, rather easily’ because it is a relatively progressive enclave. ‘If we can’t do it here -- when everyone’s feeling good and giving high-fives–then we’re in trouble’”). Unfortunately this “historically unprecedented moment of opportunity as young artists” as Clare Chase stated in her graduation speech at Northwestern University (and Will quotes in the dissertation), is not referring to everyone. In today’s hyper-segmented society with a vast universe of metaphorical background “noise”, how can one establish a signal bright enough that will bring enough attention to allow a sustained and continued musical career, if you are not a white male, under 40 years old? One way is to have benefactors/mentors to help advocate your way forward; when Meryl Streep was just trying to get her way into the door with Kramer vs. Kramer she had some early help that, if wasn’t there, the world could have missed out on the future MERYL F**KING STREEP: Getting Meryl [Streep] past the studio hadn’t been easy. Some of the marketing executives at Columbia thought she wasn’t pretty enough. “They didn’t think that she was a movie star. They thought that she was a character actress,” Richard Fischoff said, describing exactly how Meryl saw herself. But she had her advocates, including Dustin Hoffman and Robert Benton, and that was enough to twist some arms. (Vanity Fair, March 2016) Or this story of film composer Bear McCreary getting his break through a chance meeting, which helped him meet a composing idol: And quite frankly, I think the only reason that a 24-year-old kid with no credits is the composer of Battlestar Galactica is because it was a television show… [Bear] McCreary's career goes back to a chance encounter when he was a junior in high school. The local rotary club in Bellingham, Wash. named him "student of the month," and at the awards luncheon it came up that he was interested in film music. After the event, a man named Joe Coons came up to him and told him he had a friend in the business. And I thought, 'All right, whatever, man,' McCreary recalls. And he says, 'Have you heard of Elmer Bernstein?' And my jaw hits the floor. I mean, this guy had written some of my favorite melodies, ever"….That's how I met Elmer Bernstein. And I ended up working for Elmer for seven to 10 years. Honestly, it’s hard to fathom that a 24-year old black or brown kid with no film or TV credits (and who didn’t have Elmer Bernstein opening doors, or more sadly, even if they did) ever getting to even BE in a position to get that kind of opportunity with a major studio production (hey Marvel, while I have written music for film, I would LOVE to have that “McCreary shot” for the upcoming Black Panther (or Captain Marvel) movies... I'm serious--you know where to find me…). Actually Bear’s story illustrates two points about how composers can get the opportunity to flourish: one, he got to meet an advocate, who while offering advice, also helped open doors; but the second, more salient point was that he had a network that included friends and acquaintances that had access to someone influential and necessary in helping to get the opportunity to even start his trajectory in the first place. In my thesis I quote composer/vocalist Shara Worden (now Nova) from the article “Playing Between Rock and a Classical Place” (Wall Street Journal, Jan. 15, 2011) encapsulating some of the interconnectedness baked into the indie classical scene: The really beautiful thing is that it's really based on friendship. There's a crew of us, and it's a bit incestuous. This quote always bothered me. Now, I understand and actually agree with the basic premise of what she is saying: life’s too short to waste time and energy on crazy so that working with friends, people you know, like, and are comfortable with is joyous and rewarding. But in its effect, it feels a little like “cafeteria tribes”—if you are lucky enough that your tribe includes people who are already “in” (or can more easily GET in) and then can hold the doors open for friends, everything is great. It reminds me of a little like living in New York: if you have lots of money, the city can seem to offer unlimited possibilities and pleasures; if you don’t, it’s a different city of constant struggle and hustle…with few pleasures. Now this illustrates some of the implicit privilege or luck, which is in the DNA of the system for some. This ties directly into answering Will’s question about what kind of composers get to flourish in the current environment (and partly, the how), I believe luck is preparation meeting opportunity. If you hadn’t been prepared when the opportunity came along, you wouldn’t have been ‘lucky.’” Could I ever say with a straight face that luck played no role in my career? Of course not. There are plenty of talented writers out there who don’t have the good fortune to have friends already working in media who will invite them to a party where they may make a connection that will change the rest of their lives. But as I also explained in my interview with Levo League, I work extremely hard. I try always to be prepared so that when an opportunity comes along, I’m ready to make the most out of my lucky break. After getting my book deal, I turned in a finished book in six months while simultaneously finishing a master’s degree at Columbia University. That part, and the positive reviews that followed, had nothing to do with luck. That, as Sklar might say, was all my sweat and ‘giving a damn’ (http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/05/19/i-m-not-ashamed-to-admit-i-got-lucky-and-neither-should-you.html). Of course, having the luck/privilege of going to the “right” school, living in the “right” neighborhood, having the “right” background, financial stability, and friends all goes in to helping some have the opportunity to be in a position to be able to give all your “sweat” and a “damn”, which more likely can lead to early success. But what is success or flourishing as a composer anyway? Commissions from classical music institutions? Putting out well-received recordings? Ability to tour? Making your living off of music? Getting tenure at a university? Having Philip Glass as a mentor? Certainly the answer is different for everyone, but as Will states above, the possibility of achieving whatever one’s definition of success is, is more and more “complicated and bleak” in today’s society, even for the privileged. Success/flourish is obviously often not one or two points but a continuum, a cloud if you will, that is built upon by various steps over time; the accumulation of the “right” elements, which are different for different people—family and musical background & experiences, temperament, talent, social network circumstances & opportunities, and just plain luck—that builds upon itself (the cloud metaphor is appropriate here: not only in how clouds form, but also as seen from afar—they look formful & defined, but upon closer inspection you realize that where it begins is often undefined and diffused but once you are fully in it, you know). Like how people talk about the achievement gap, if you don’t start off with the opportunity to accumulate those first steps in development then you are always playing “catch up” and you’ll face stiffer and deeper difficulty than if you had the plow cleared for you early on (and this doesn’t mean one CAN’T make headway to overcome the deficiencies, just means more struggle to achieve). So reading Will’s dissertation I remarked at the “general similarity of experiences, backgrounds, and socio-economic status” of the people written about (young-ish, white, mostly male, middle/upper middle class, Ivy League educated), and, while the ones I know personally are some of the hardest working people I’ve met, they nonetheless have benefited because of “the academic settings, institutional ties, and privileged backgrounds that have allowed this generation to flourish, the rhetoric of ‘honesty’ and ‘naturalness’ in ‘music without walls’ runs the risk of misleadingly valorizing entrepreneurship. As Andrea Moore has documented, the promotion of arts entrepreneurship is increasingly common among music schools in the United States. When careers of such ‘self starters’ as [Nico] Muhly, [Judd] Greenstein, and [Missy] Mazzoli are used as models for such programs—without necessarily telling the ‘full story’ of their musical backgrounds—it can perpetuate false narratives of replicable success (Robin, pages 260-61).” I often think about those many others not in the scene—those not already in resonance with critics whose “personal histories… are drawn to something that they were each already, in a way, looking for” (Robin, page 96); those “…African American experimental musicians…often ignored or critiqued by writers who subsequently lionized the comparable boundary crossing of white artists…” (Robin, footnote #34); those black artists that “channel R&B, funk, and hip-hop, while their white contemporaries get kudos for giving makeovers to the likes of Radiohead, Nick Drake, and Bjork” (Interview with John Murph on Open Sky Jazz “Ain’t But a Few of Us: Black jazz writers tell their story Part 2”; those composers discussing and building their own wonderful scene of community and support on #Musochat—that given similar chances (and frankly luck/fortune) could create and develop into similar levels of success and acclaim but find it increasingly more difficult with the decks more stacked against, and “the mechanisms that allowed indie classical to gain prestige and institutional support have been disrupted. Future cohorts of composers will continue to emerge, but is not clear how they will transform cultural capital into economic capital to create the kind of sustainable careers that New Amsterdam has sought for its artists. The rhetorical positioning of indie classical—that it came into existence outside the ‘strictures’ of the concert hall and the academy—may create the false impression that the next generation could thrive without the traditional infrastructure of classical and new music.” (Robin, pages 260-61). The path(s) taken by those younger composers in the dissertation, which itself was/were originally blazed by those composers in the 60s and 70s, to take advantage of Claire Chase’s “historically unprecedented moment” is/are harder and harder to see for more and more composers now, but especially composers of color. Many years ago I used to substitute teach in NYC public schools. I went to schools all over the city—anywhere from the Upper West Side in Manhattan and Park Slope in Brooklyn to East Harlem—and was always shocked by the disparity between the amount of resources available to those schools in wealthy neighborhoods compared to those in less affluent areas. Now in every school and neighborhood there were smart, inquisitive students (and also those less so); but always with the less wealthy schools, I would lament for those talented, smart black and brown faces I saw (because that’s usually the only faces I did see in those schools) because I just wished that those kids could have had the chance to be in a school environment with the same resources, to have similar life experiences that I found with the students in the richer areas. Of course I did not wish those kids in the wealthier districts didn’t have what they had, I just wanted something similar for all those other talented kids in the other districts, who I KNEW would benefit from the same opportunities those Upper West & East Side/Park Slope/Carroll Gardens/Brooklyn Heights kids had—a good chance to fulfill their full potential; I SAW and FELT the gaping disparity and but for the factor of circumstances they didn’t control, those kids COULD have had but didn’t. And reading the dissertation, while happy for how some composers were able to rise above to be heard and noticed, I also felt that same pang for all of those other composers out there that would not get the same chances. How can it change? Well one way, short of having more POC and women in boardrooms making programming decisions or others on the "inside" the club to look "outside", maybe there needs to be some kind of indie classical/new music “Rooney rule”. While not perfect, the Rooney rule has helped people of color in the NFL to be considered to high level positions. So next time a symphony or institution relies on the bromides about how they can’t ‘find’ women or black/brown composers or when they say, “Hey what about [any-number-of-names-we’ve-heard-before-and-who-will-be-fine-if-they-don’t-get-that-commission/award-from-your-esteemed-organization] for that commission maybe the Rooney rule could be there to say, ‘you know, there are other great composers out there that aren’t friends/acquaintances/people someone went to school with/in our usual circle, let’s find out more about them.’ Hey, as I said in a tweet: Black and brown composers don't want to be tokens or diversity experiments but, like any composer, just want the same opportunity to “get in the room…to have a real chance..." as anyone else; and, we'll take it from there.

|

The NuminosumTo all things that create a sense of wonder and beauty that inspires and enlightens. Categories

All

|

Thanks and credit to all the original photos on this website to: David Andrako, Concrete Temple Theatre, Marcy Begian, Mark Elzey, Ed Lefkowicz, Donald Martinez, Kimberly McCollum, Geoff Ogle, Joseph C. Phillips Jr., Daniel Wolf-courtesy of Roulette, Andrew Robertson, Viscena Photography, Jennifer Kang, Carolyn Wolf, Mark Elzey, Karen Wise, Numinosito. The Numinous Changing Same album design artwork by DM Stith. The Numinous The Grey Land album design and artwork by Brock Lefferts. Contact for photo credit and information on specific images.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed