| Numinous The Music of Joseph C. Phillips Jr. |

The Numinosum Blog

The next Composer Salon is on Monday May 10th, 2010 from 7 pm to around 9 pm at the Brooklyn Lyceum (227 4th Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn), FREE! The Lyceum is literally above the Union Street M, R Train stop in Brooklyn. The Lyceum does have various inexpensive libations including different beers, wine and other non-alcoholic beverages, as well as coffee and baked goods. If you are a composer/musician in New York City area, regardless of genre, style, or inclination, I hope you can come out, meet some new and old faces behind the blogs and comments and listen or join the discussion, which often branches out from the original topic. With last week's 'alt-classical' blogosphere 'debate' about the influence of popular music in the works of some composers, I did think about using the flare-up as a subject for discussion at this month's Salon (despite basically already talking about a parallel subject back in November 2009). However with people such as Matt Marks, 8th Blackbird, Brian Sacawa, Dennis DeSantis, et al. covering things pretty well (and which I burned a few brain cells in some 'rants', ah, comments on a few of the blogs) and seeing as most of the rest of my brain power these days has to be devoted to getting ready for a couple of Numinous shows in the upcoming weeks, I thought I'd bring back one of my old topics, to make my life a little easier for this month's Salon. Salon Topic #6: Form Here's some olden thoughts: “If you want to create a work of art that is unified in its mood and consistent in its structure, and if it is to give the listener a clear and definite impression, then what the author wants to say must have been just as clear and definite in his own mind. This is only possible through the inspiration by a poetical idea, whether or not it be introduced as a programme. I consider it a legitimate artistic method to create a correspondingly new form for every new subject, to shape neatly and perfectly is a very difficult task, but for that reason the more attractive. Of course, purely formalistic [music-making] will no longer be possible, and we cannot have any more random patterns, that mean nothing to the composer or the listener…”-Richard Strauss in a 1888 letter to Hans von Bulow “[in his first period] traditional and recognized form contains and governs the thought of the master; and the second [period], that which the thought stretches, breaks, recreates, and fashions the form and style according to its needs and inspirations.”-Franz Liszt in a 1852 letter to author Wilhelm von Lenz, writing of Beethoven “[Marcel] Breuer was aware of the significant value of spontaneity and freshness to design and it is still my inclination to work in that manner. It is easy to complicate matters and be trapped by the multitude of design and technical solutions requiring resolution on all projects. Loss of momentum is, generally, disastrous. Relatively little seems to be achieved by reworking and reconsidering matters time and time again. There is no stopping point in design and one could go on designing forever, but the degree of improvement on a project diminishes precipitously at a sometimes hard to recognize point.”-David Masello in Architecture without Rules And some more contemporary takes: “What I really try to do is start from zero…I’m trying to start as much as I can from a neutral point, to see what the first impulse is and work from that…sometimes I’ll start with a technical idea…sometimes an image will come up of what the whole piece will be, and then it’s a matter of finding the components and structuring it. Generally, the process begins intuitively and I try to stay out of the way of the material as much as I can. Then as it goes along, the intellectual aspect comes in, which is trying to find the correct form for that material.”-Meredith Monk from New Voices: American Composers Talk about Their Music “To realize I can reinvent form every time I write is daunting. But often what I want is to open up and tell a story. I want people to feel like my music takes them on a journey, brings them [to] different places, enticing or surprising them. I develop the form based on my dramatic needs…”-Maria Schneider from an interview with Fred Sturm Basically the question is how do we organize and make sense out of the music that we hear and that we create? If you are a composer or musician or music lover in the New York City area, consider coming down to the Lyceum and joining the discussion, or if you don't live in New York or can't make it, adding your thoughts in the comments. Hope to see you on May 10th! Previous Composer Salons Composer Salon #1: The Audience Composer Salon #2: Future Past Present Composer Salon #3: Mixed Music-Stylistic Freedom in the 'aughts Composer Salon #4: Inspiration Composer Salon #5: What Do You Mean? (also here's a NPR A Blog Supreme article about the Salon) POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 8:00 AM

0 Comments

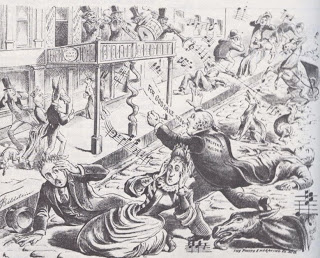

The next Composer Salon is on Monday March 15th, 2010 from 7 pm to around 9 pm at the Brooklyn Lyceum (227 4th Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn). And the price is right: FREE! The Lyceum is literally above the Union Street M, R Train stop in Brooklyn. The Lyceum does have various inexpensive libations including different beers, wine and other non-alcoholic beverages, as well as coffee and baked goods. If you are a composer/musician in New York City area, regardless of genre, style, or inclination, I hope you can come out, meet some new and old faces behind the blogs and comments and listen or join the discussion, which often branches out from the original topic (at the end of this post are links to previous Salon topics as well as an article on NPR's A Blog Supreme about a recent Salon-don't worry, this next one will be a bit warmer than the last!). Salon Topic #5: "Music is the universal language of mankind."-Henry Wadsworth Longfellow What is communicating meaning in music? Is music's meaning defined by how it is used, borrowing an idea of Ludwig Wittgenstein? Music in a film, is film music; if it is played at Birdland or the Village Vanguard, it is jazz; if the New York Philharmonic plays it, it must be classical, etc. Or does music mean little more than sounds in time, as Igor Stravinsky writes in his An Autobiography, "I consider that music is, by its very nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all, whether a feeling, an attitude of mind, or psychological mood, a phenomenon of nature, etc….Expression has never been an inherent property of music. That is by no means the purpose of its existence." For that matter what do the labeling of music convey and mean? When someone says 'classical music' or 'jazz' (or 'anti-jazz') or alternative, what does that even mean? While many of today's composers and musicians eschew labels and genres, many others often proudly define themselves by choice: jazz composer, classical musician, rock band, rapper, etc. And when they don't define their music explicitly, their associations often betray their proclivities. Isn't one of the first questions a musician is asked when introduced to a non-musician is, well what kind of music do you write/play? Doesn't that answer affect what someone thinks about your music (and you)? Once someone knows what kind of music you write/play, accurately or not, they feel they understand it (you) and they know what it (you) means. So what does labeling one's self mean to one's music? If "music is music," as Alban Berg said to George Gershwin when Mr. 'Fascinating Rhythm' was hesitant to play piano for Mr. 'Wozzeck' on their first meeting, then why self-select a genre? Many a sensitive and creative artist wants to communicate and connect with the public. Which often translates into conveying a particular meaning to our work (whether we make that meaning explicit or not). However what happens when the listener (consumer) takes another meaning away from our work? Is this valid? Should we clarify to the public our objectives toward what the work means so as not to be misunderstood? Or should we just write and play, and let the meaning come what may. After-all, as T.S. Eliot said, “Great art can communicate before it is understood.” I. What does music mean? This evocative question was the title of Leonard Bernstein’s first televised New York Philharmonic Young People’s Concert in the late 1950’s. Fifteen years after that first concert, the third of Bernstein’s six Norton Lectures at Harvard University asked this same question. Brilliantly comparing the musical language to some of the ideas of linguistic theory, specifically Noam Chomsky’s universal and transformational grammar, Bernstein says, “Music has intrinsic meanings of its own, which are not to be confused with specific feelings or moods, and certainly not with pictorial impressions and stories. These intrinsic musical meanings are generated by a constant stream of [musical, extrinsic, and analogical] metaphors…” While not quite as rigid as Igor Stravinsky’s famous saying that music has no meaning (“music’s exclusive function is to structure the flow of time and to keep order in it”), Bernstein’s definition is similar to Aaron Copland’s position in What to Listen For in Music, “all music has an expressive power… all music has a certain meaning behind the notes… [the music] may even express a state of meaning for which there exists no adequate word in any language.” What does music express to you? What particular musical metaphors do you use to help the listener hear what you are trying to say in your compositions? What sparks the genesis of a composition for you-is it purely manipulating musical ideas, concrete extra-musical associations, and/or metaphorical expression? All of the above? II. Music, like language, is about and has always been about communication. From the performer/creator, some meaning and/or expression is transferred to the listener through, what 19th century music critic Eduard Hanslick calls “sonorous forms in motion”. Often what is transferred to the listener is not particularly definable or if it is, it is often not particularly what the performer/creator had in mind while creating the work. In the wonderful book (which I've recommended before) New Voices-American Composers Talk about their Music (Amadeus Press, 1995) Laurie Anderson speaking about communicating ideas to her audience says, “…to me the richer the image is, the better. By richer I mean clearer. It has no obstructions, it gets right across and people can understand it…I’ve chosen to be an artist and half of that, at least is in the communication of it.” She goes on later in the interview to say, “And I feel that the work has really succeeded when somebody says, ‘I saw or heard your piece and I got so many ideas from it’. Then they tell me what the ideas were, and they’ve nothing to do with what I was doing. That suggests to me that the piece was rich enough for them to take something from it and do what they wanted.” How do you insure that your compositions are clear to you? To the listener? If you feel your compositions present understandable ideas/feelings/expressions, is it successful if it conveys to the listener ideas/feelings/expressions entirely different from your original intent? Is this important to you? If you are a composer or musician or music lover in the New York City area, consider coming down to the Lyceum and joining the discussion, or if you don't live in New York or can't make it, adding your thoughts in the comments. Hope to see you on March 15th! Previous Composer Salons Composer Salon #1: The Audience Composer Salon #2: Future Past Present Composer Salon #3: Mixed Music-Stylistic Freedom in the 'aughts Composer Salon #4: Inspiration (also here's a NPR A Blog Supreme article about the Salon) (Photo credits: public domain image from the cover of the newspaper The Mascot from http://www.kimballtrombone.com/) POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 8:18 PM Just a quickie post: on Friday Lara Pellegrinelli wrote a good feature on NPR's A Blog Supreme about my last Composer Salon on Inspiration (January 2010).

Keep checking back for details on the March Salon. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 1:49 AM Monday night, February 1st is the 6th anniversary of Janet Jackson's infamous breastcapade in Super Bowl 38. It is also the next Composer Salon from 7pm to 9pm at the Brooklyn Lyceum (227 4th Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn: literally above the Union Street M, R stop). While I can't promise there will be any wardrobe malfunctions, there certainly will be good discussion of the topic, Inspiration. Hope to see some of you on Monday.

POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 7:51 AM The next Composer Salon is on Monday February 1, 2010 from 7 pm to around 9 pm at the Brooklyn Lyceum (227 4th Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn). And the price is right for our troubled economic times: FREE! The Lyceum is literally above the Union Street M, R Train stop in Brooklyn. The Lyceum does have various inexpensive libations including different beers, wine and other non-alcoholic beverages, as well as coffee and baked goods. If you are a composer/musician in New York City area, regardless of genre, style, or inclination, I hope you can come out, meet some new and old faces behind the blogs and comments and listen or join the discussion. Salon Topic #4: “You need a certain dose of inspiration, a ray from on high, that is not in ourselves, in order to do beautiful things….”—Vincent van Gogh, in a letter to his brother Theo “Basically, music is not about technique, it’s about spirit.”—Terry Riley As some of you know in June 2010, I'll be premiering one section of a new collaborative project based upon the writings of Thomas Paine, To Begin the World Over Again with Numinous, dance choreographer Edisa Weeks, and her company Delirious Dances. The full project will take place in the spring of 2011. In my research and reading for the project, I read David McCollough's wonderful book 1776, a riveting account of that pivotal year in American's revolution against England. And while the book only talks about or mentions Thomas Paine briefly, both occasions were stirring. One was an account of the retreat of the American troops from New York City to New Jersey and the famous crossing of the Delaware River. Thomas Paine, who as an aide to General Greene, was among the retreating troops. Inspired by the American's incredible resolve and determination against frigid weather and a seemly invincible opponent, Thomas Paine began writing the words which eventually became his American Crisis. Whose famous words, "these are the times that try men's soul's" echo the graveness of the times then and have been appropriated by many since then. The other account in 1776 was an aside about how Common Sense, which was published on January 9th, 1776 (not the 10th as is commonly thought), was read to the soldiers of the fledgling colonial army and how the moving words of Common Sense changed the conflict in the minds of those soldiers (as well as in the mind of General Washington) from a struggle against the meddlesome but generally welcomed rule of a benevolent crown to a war for freedom and independence against a foreign invader. I thought about how the words of Thomas Paine inspired the Revolution and recently it got me think more generally about inspiration itself. Last week, I, along with my Pulse colleagues Darcy James Argue and JC Sanford, were a part of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT) where we were commissioned by founder Dave Douglas to write 'arrangements' of Ornette Coleman tunes. Before our concert was a performance of composer Charles Wuorinen's brass music. At the conclusion of the Wuorinen concert, I was talking with a fellow composer who remarked, something to the effect of how they were "amazed at what different music is in people's heads." This was not meant as a direct criticism of the Wuorinen music we just heard, but rather a general wonderment at how different people hear different things and how that manifests itself in sound and music. Certainly Charles Wuorinen's soon to be completed opera Brokeback Mountain will sound completely different than Gustavo Santaolalla's score to the movie? And what a different creation is the movie when compared to the Annie Proulx's short story? How does the same short story inspire such different outcomes? What inspires someone to compose the way they do? I also thought about the great music Darcy, JC and myself came up with in reimagining Ornette Coleman's music into something new. What inspired us to hear Coleman's music in such a way that, while certainly referencing Coleman, sounded less like Coleman and more like Darcy, JC, and me? It is really fascinating to contemplate (well, at least to me anyway) and I thought the idea of inspiration might be an interesting discussion for others in the Composer Salon as well. I. German poet Rainer Maria Rilke said, “always at the commencement of work that first innocence must be reachieved, you must return to that unsophisticated spot where the angel discovered you when he brought you the first binding message.” How do you approach the start of a new composition? What inspires you to begin a composition? Is it purely the working out of musical material, an extra-musical association, or a combination that inspires the beginning of a work? II. Composer George Crumb states that in composing “there’s always a balance between the technical and the intuitive aspects. With all the early composers, all the composers we love, there was always this balance between the two things…that’s what all music reflects.” How do you reconcile and balance the two forces? Do you really need to? III. Composer Alvin Lucier, in his essay The Tools of My Trade, speaks of a temptation, when first conceiving a piece, “towards greater complexity” in his principal musical idea, but eventually reducing the idea to its’ minimum. This idea of reducing ideas to only their barest essence (and the difficulties inherent in that) is also spoken about by Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Mark Rothko and many other artists, writers, musicians (as well as philosophers and theologians). Do you fight the temptation of “greater complexity” in your own music? How do you do it? What ways/techniques help you achieve the 'right' way to convey your musical idea(s) in your composition? When do you know if it is 'right'? If you are a composer or musician or music lover in the New York City area, consider coming down to the Lyceum and joining the discussion, or if you don't live in New York or can't make it, adding your thoughts in the comments. Hope to see you on February 1st! Previous Composer Salons Composer Salon #1: The Audience Composer Salon #2: Future Past Present Composer Salon #3: Mixed Music-Stylistic Freedom in the 'aughts POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 12:02 AM  It's time again for the next Composer Salon on Tuesday December 8, 2009 from 7 pm to around 9 pm at the Brooklyn Lyceum (227 4th Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn). The Lyceum is literally above the Union Street M, R Train stop in Brooklyn. The Lyceum does have various inexpensive libations including different beers, wine and other non-alcoholic beverages, as well as coffee and baked goods. If you are a composer/musician in New York City area, regardless of genre, style, or inclination, I hope you can come out, meet some new and old faces behind the blogs and comments and listen or join the discussion. Salon Topic #3: “What makes the history of music, or of any art, particularly troublesome is that what is most exceptional, not what is most usual, has often the greatest claim on our interest. Even within the work of one artist, it is not his usual procedure that characterizes his personal ‘style’, but his greatest and most individual success.”—Charles Rosen, The Classical Style On November 19th, I attended the 21cLiederabend concert at Galapagos Art Space in Brooklyn's fashionable neighborhood of DUMBO. The performance, co-produced by Galapagos, VisionIntoArt, Opera on Tap, and Beth Morrison Projects, was billed as "a multimedia performance featuring vocal works by some of New York's rising young stars of post-classical composition." Composers Caleb Burhans, Leah Coloff, Corey Dargel, Osvaldo Golijov, Judd Greenstein, Ted Hearne, David T. Little, Missy Mazzoli, Nico Muhly, Milica Paranosic, Kamala Sankaram, and Paola Prestini all had pieces performed and while I enjoyed most of the compositions (some quite a lot: Greenstein's "Hillula", Golijov's "Lua Descolorida", and Mazzoli's "Song from the Uproar" were three of my favorites) at some point during the show, as I listened to the works brimming with compelling ideas and sounds, I began to wonder what music historians will make of our age. Almost all of the compositions had a seriousness purpose, to be expected from the erudite and aware composers. Happily, for me anyway, while there wasn't any real stylistic unity between the compositions, there were a few things in common. One was that each composition seemed to be intent on working a 'new beauty' aesthetic: generally euphonic sounds (even the dissonances) with a more contemplative (not necessarily slow) musical tone. Second was that all of the pieces seemed to be what I call, mixed music: music that goes beyond the rigid definitions of a singular genre to organically fuse multiple styles into something completely different (think how children of mixed race couples are neither one yet both of the races of their parents). For example, the compositions at Galapagos were clearly influenced in form, instrumentation, and rhythmic and harmonic adventurousness by classical music but also included elements from other more popular musical forms and cultural sensibilities (whether pop, rock, hip-hop, etc.). Other terms for this type of composition in the classical world are alt-classical or post-classical, but I think my term mixed musicbest describes this trend in music because it can reflect many different hybrids of styles: from the jazz world (groups such as the Bad Plus and Darcy Argue's Secret Society mixing the jazz and rock/alternative worlds; Robert Glasper's work with Q-Tip, Kanye West, Mos Def, and Maxwell or Roy Hargrove playing with D'angelo or most of MeShell Ndegeocello's output all working the jazz and creative black popular music angle (sometimes with a decidedly Prince-ian eclecticism and élan); contemporary classical and pop or electronica (Nico Muhly or the new In C Remixed recording) or my own compositions with Numinous, which fuses elements from contemporary classical and jazz to other more popular forms). While there is much fundamentalism and narrow-mindedness in values and taste in today's society, which is often defended in the most obstreperous manner leading to more and more ossification of those values and tastes (think of the political climate in the US and you get what I'm saying), I could argue that this entire generation or era is one of mixed sensibilities: racially, financially, temporally, and culturally. Even though I'm not one for labels since they usually only hint at something and are partially accurate at best, I do understand in the 'real world' that they are necessary so the term mixed music seems an appropriate one to describe much of the music of our time, at least in much of the creative artistic music with its heterodox movement toward a 'beyond-genre-ness'. But there is a danger with no overarching stylistic unity or this blending of styles and influences to center or ground a composer, similar to what Leonard Bernstein discussed about music's meaning and intelligibility in his Norton Lecture "The Delights and Dangers of Ambiguity": what makes a composer's voice consistent and understandable from piece to piece? At the 21cLiederabend concert I was reminded of Wassily Kandinsky’s discussion of Pablo Picasso's style in his Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Of Concerning the Spiritual in Art). Speaking of Picasso he writes: “Tossed hither and thither by the need for self-expression, Picasso hurries from one manner to another. At times a great gulf appears between consecutive manners, because Picasso leaps boldly and is found continually by his bewildered crowd of followers standing at a point very different from that at which they saw him last. No sooner do they think that they have reached him again than he has changed once more.” With all of the stylistic borrowing, how do you make something that isn't pastiche? What filament runs through someone like Picasso to make it Picasso? I mean Steve Reich sounds like Steve Reich. John Adams, John Adams. Philip Glass, Glass. Charlie Parker. Bird (well, I guess you could say Sonny Stitt also sounds similar to Bird, but that's another discussion; on the Jazz Loft Project Episode #10 listen to pianist Paul Bley talking about finding one's own sound after Charlie Parker died). But listening to the composer's compositions on November 19th, what thread runs through their works? Besides their names on the scores, what makes a piece by Missy Mazzoli, Missy Mazzoli's? Nico Muhly, Nico Muhly's? Joe Phillips, mine? And, of those on the Galapagos concert, asking the question Norman Lebrecht asked in his recent poll of composers we'll still be listening to 50 years from now, whose sound and music will we be hearing from 50 years from now? 100 years? 10 years? Does it really matter? To relate to the Charles Rosen quote above, is all of this stylistic borrowing and the music that encompasses it, what is 'exceptional' in our age or usual? Years from now, what will mark people's interest in the music of now? So here are a few thought-provoking statements and fodder for discussion relating to style and the freedoms (and limitations) in our mixed musicera: I. Arnold Schoenberg writes in his Die Musik, “Every combination of notes, every advance is possible, but I am beginning to feel that there are also definite rules and conditions which incline me to the use of this or that dissonance.” What are the rules now? Is it rules or just taste? Whose taste dictates what is 'good'? II. Jazz composer, pianist, and AACM founding father Muhal Richard Abrams tells Francis Davis in a February 1991 article, “In the beginning, jazz was an abstract process. It wasn’t any particular style yet. It sounded like whatever the musician wanted it to sound like. It stood for the freedom to experiment, the excitement of things never quite coming out the same.” Do you feel jazz has moved away from the inclusive origins Abrams talks about? Is that spirit and 'freedom to experiment' alive in today’s jazz? How do you balance experimentation with standard practice in your own music? If it sounds like 'whatever you want it to sound like' why identify yourself as a 'jazz' composer? a classical composer? a pop musician? etc. III. Composer Daniel Lentz says, “style is really just learning how to repeat yourself, sometimes endlessly. If you keep changing your language and what you do, which is a very noble thing to do, nobody will know who you are?” Do you agree with this statement or not? Thinking about the Kandinsky quote on Picasso, do you strive for a “coherence or singularity” in your musical language or is your language "tossed hither and dither"? What characteristics would define your own personal style? IV. Morton Feldman writes in his essay "The Anxiety of Art", “The painter achieves mastery by allowing what he is doing to be itself. In a way he must step aside in order to be in control. The composer is just learning to do this. He is just beginning to learn that controls can be thought of as nothing more than accepted practice.” Is control nothing more than “accepted practice”? How do you control and manage the flow and freedom of ideas during the composing process? How does this relate to the Daniel Lentz quote above? If you are a composer or musician or music lover in the New York City area, consider coming down to the Lyceum and joining the discussion, or at the very least adding your thoughts in the comments. Hope to see you on December 8th! POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 5:19 PM It's time again for another Composer Salon. The last one in September on the topic, The Audience, was a good time with a lively and fun discussion. The next Salon is:

Tuesday October 20, 2009 from 7 pm to around 9 pm at the Brooklyn Lyceum (227 4th Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn). The Lyceum is literally above the Union Street M, R Train stop in Brooklyn. The Lyceum does have various inexpensive libations including different beers, wine and other non-alcoholic beverages, as well as coffee and baked goods. Salon Topic #2: With some topics I read on various blogs recently (which you can find the links to below) I thought the subject of where classical music and jazz are headed to leads to this month's Salon topic: Future Past Present. This quote from Hannah Arendt, which I think I first read in the liner notes to the Dave Douglas CD Five, seems to fit with my thinking about where both classical and jazz at the moment (or at least where it should be going): There is an element in the critical interpretation of the past, an interpretation whose chief aim is to discover the real origins of traditional concepts in order to distill from them anew their original spirit which has so sadly evaporated. I. Pat Metheny in his keynote address to the (now defunct) International Association of Jazz Educators (IAJE) convention in 2001 challenged musicians “to recreate and reinvent the music to a new paradigm resonant to this era, a new time.” Not to recreate the past, but to push and remake music of and for our own generation and time. Like the first line in the Stephen George poem "Entrückung" that Arnold Schoenberg set in his groundbreaking Second String Quartet, I also feel the “Luft von anderem Planeten" ("the air from another planet"). There does seem to be something in the zeitgeist where “artistic” composers and musicians are thinking beyond genre and really seeing the popular music of their times as valuable sources of inspiration (let alone for plain guilt-free enjoyment). I'm actually very excited with what is happening with this development in art music (something that I, along with many in my and younger generations have felt along) but frustrated in the continued old ways and thinking that seem to dominate much of the cultural artistic space. I am hopeful though because like Sam Cooke sang, "a change is gonna come..." How do you address Metheny’s sentiment in your own work? Or do you feel it is even important to do this? II. In an interview years ago composer John Adams was asked the question: What's your opinion of the future of the orchestra? I think his response was quite telling coming from one of America’s leading composers of orchestral music: “When people ask that question I have to be quite blunt: I think the orchestral tradition has pretty much come and gone. There are periods in which a certain artistic genre sees a birth, a flourishing and then an eventual decline. It doesn't matter whether it's Elizabethan drama or Italian madrigal or the Homeric epic. Every genre eventually passes from the scene. Orchestral music reached its peak around 1900, and there's been a period of natural decline ever since. Look at how few substantial additions there have been to the repertoire since 1950 - it speaks for itself.” From my viewpoint it seems that orchestras and orchestral music is quite entrenched, well at least as far as cultural dollars go. In the comments of a posting on Greg Sandow’s blog about classical music’s presentation problem, I said, “Certainly the large classical institutions draw a lot of financial oxygen from any market. $10,000 or $20,000 might not make much difference to the NY Phil, but make it an easily available grant to a hungry new music outfit, I think you would immediately see more diverse, daring, interesting (not always successful, but that's ok) programming that would attract a more diverse (racially, aged, and economically) group of people, especially if they aren't charging $50-75+ for seats, and would feel more real and relevant to the listeners.” In our society with its unacknowledged plutocratic tendencies, seems like that entrenchment isn’t going to change anytime soon. In the jazz world, Jazz at Lincoln Center operates much like the jazz equilvant of an orchestra organization. Larry Blumenfeld wrote about J@LC in the Wall Street Journal a few weeks ago and also in a blog in a post about Jazz at Lincoln Center. I commented on his blog, I think that J@LC does deserve credit for raising the bar for jazz in the upper crust circles that previously would never consider jazz worthy of support. However, with such a mark of status, J@LC could be so much more. I think there is frustration that the conservative attitude at J@LC by freezing jazz in amber freezes out many great musicians who don't fit the model. And without any real choice or competition, there doesn't seem to be any (or very little) institutional avenue for more contemporary and progressive takes of what jazz is. The only major jazz institution with any clout really is J@LC and that's frustrating. In the classical world, sure you can have some fundamentally conservative and cautious organizations like the NY Phil and the Met (both which are disappointing in similar ways as J@LC, although under Gelb at least the Met is moving in a different direction), but that is more than offset by other adventurous organizations such as the SF Symphony or even Bang on a Can. Where is the Bang on a Can-like organization for jazz? If there were some competition for the 'jazz dollar', some other high profile organization to take on music/groups/composers that which J@LC won't or can't, some one other than Wynton to be able to bend the ear (and get the eye) of Obama and Clinton, I bet there would be less animosity toward Wynton and J@LC because he wouldn't be the only gatekeeper, his voice would be balanced by a competing voice. Just as you could never have a working class person run for state-wide offices in today’s society because the amounts of money needed for a campaign, how can the non- institutional groups, ensembles, performers of classical and jazz many of which often are pointing to new and exciting directions for the music (and where my hope for the future of the music lies), ever hope for the recognition and dollars (which in itself can represent status), if they don’t have the resources to compete? Sadly in many ways, this seems to me a class struggle between the haves (large orchestra and opera companies or J@LC in the jazz world) and the have-nots or has a little (smaller organizations and ensembles) fighting for survival in genres that generally speaking, very few are listening to or are much interested in. So since classical and jazz are just niche markets that are shrinking in the music marketplace, have we hit that decline that John Adams talks? As Greg Sandow says in the above blog post, is it the music or the presentation? If we change either, will people listen and the music become more relevant? More listened to? Where is the music going and what is it evolving into? Do all of the social networking media, blogs, and direct marketing over the Internet affect what classical and jazz are? Will become? If you are a composer or musician or music lover in the New York City area, I hope you'll consider coming down to the Lyceum and join the discussion, or at the very least add your thoughts in the comments. Hope to see some of you on the 20th. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 9:42 PM A number of years ago I started a composer's salon here in New York City to foster discussion on topics dealing with music issues. It was an opportunity for a group of composers and musicians to sit down together with good food and drink and talk (and argue) about various ideas and questions in a collegial atmosphere of learning. The talks were quite interesting and often lead to insights far a field from the original topic and subject; the recommendations and listening of various recordings of composers and groups I didn't know, for me, was a wonderful benefit to the Salon. So I thought I would reboot the discussions with the first of Composer Salon 2.0.2 on:

Tuesday September 22, 2009 from 7 pm to around 9 pm at the Brooklyn Lyceum (227 4th Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn). The Lyceum has graciously offered their cafe space for these Salons and is quite convenient to get to, literally above the Union Street M, R Train stop in Brooklyn. The Lyceum does have various inexpensive libations including different beers and other non-alcoholic beverages, as well as coffee and baked goods. If you are a composer/musician in New York City area, regardless of genre, style, or inclination, I hope you can come out, meet some new and old faces behind the blogs and comments and listen or join the discussion. My plan is to post a new discussion topic a few weeks before the actual Salon which hopefully will provide manna to a good discussion. The night of the Salon I will put on my best Jim Lehrer and moderate things to stay (somewhat) on topic. If you don't live in New York (or can't make the Salon live), feel free to chime in in the comments on the planned topic and we can use those developments at the discussion. Salon Topic #1: Because of the hoopla with the Terry Teachout 'Death of Jazz' Wall Street Journal article (which I chose not to comment on), as well as a recent blogging conversation concerning audiences between Nico Muhly and publicist Amanda Ameer (which I did comment on), I thought I would revive and add to one of my old Salon topics, which seems quite timely at the moment: the Audience. I. In an interview (New Voices by Geoff and Nicola Walker Smith, Amadeus Press, 1995--BTW, this is highly recommended book featuring insightful interviews with many 20th century new music leading lights), Laurie Anderson says that her work/composition is not complete until it has been observed or heard [and subsequently] evaluated by an audience. She goes on to say that the measure of a good work of art is one that (as you experience it) “makes you want to jump up and get out of there” and go and create something yourself. How do you view this statement (especially in relationship toward how your own compositions are received by the public)? II. The main premise of the book Hole in Our Soul by Martha Bayles (Free Press, 1994) is that with the rise of modernism (in art) in the early 20th century, there came a disconnect with audiences—an “antagonism” between the artistic creator and the consumer of the art. Before this perverse (her words) turn of events, the relationship between creator and consumer was not so great. (At least in jazz) high art and the commercial and popular were not always mutually exclusive. As Gary Giddins states, people like Duke Ellington or Louis Armstrong had the “…ability to balance the emotional gravity of the artist with the communal good cheer of the entertainer…” However, with the advent of such movements as Dadaism or Abstract Expressionism in painting, the literary explorations of Gertrude Stein, Virginia Wolff, and James Joyce, and in music the dodecaphonic and serial explorations of Arnold Schoenberg, chance and aleatory music of John Cage and in jazz the rise of bebop and free jazz, large audiences mostly tuned out. Jazz critic Philip Larkin is quoted in Hole in Our Soul stating, “To say I don’t like modern jazz because it’s modernist art simply raises the question of why I don’t like modernist art…I dislike such things not because they are new, but because they are irresponsible exploitations of technique in contradiction of human life as we know it. This is my essential criticism of modernism, whether perpetrated by (Charlie) Parker, (Erza) Pound, or (Pablo) Picasso: it helps us neither to enjoy nor to endure.” Do you agree or disagree with Bayles’ and/or Larkin’s statements/premises? How do you as a composer/musician, balance artistic and commercial viability in your own work? In the presentation (i.e. performances) of your works? III. The recent dust-up created in the jazz world by Terry Teachout's August 9, 2009 Wall Street Journal article "Can Jazz Be Saved?" got me thinking more about how does a musician (or I guess any artist) go about creating an audience for their work. And not just an insular and incestual audience of like-minded and -aged musicians and friends, but a truly diverse cross-section of people genuinely interested in hearing the music. In the discussion between Nico Muhly and Amanda Ameer, there's talk of scenes and how they develop around record labels or the musicians on those labels. The Teachout article focuses on jazz but the same (tired) arguments have been going on for years about the aging and dying of classical music. And while the arguments have valid points, possible directions to combat 'the audience problem' are springing forth from various composers, groups, record labels, and presenters that are not complaining about the situation but seemly doing something about it: reaching beyond the classic audience-performer divide in meaningful ways and creating new and enthusiastic (if not always broadly diverse) consumers of their music. The wonderful and impressive story I read this weekend on Sequenza 21 of how composer Melissa Dunphy got the ebullient attention of MSNBC's Rachel Maddow, The Atlantic, and other non-music critics and tastemakers with her opera The Gonzales Cantata, about the testimony of former Attorney General Alberto Gonzales before Congress. No matter your thoughts on the musical merits of the work, the buzz surrounding the opera will surely widen Dunphy's audience circle beyond her family, closest friends, and general new music types. Although I'd argue that any new people most likely to resonate with The Gonzales Cantata are probably similar in makeup as those already to be found at any hipster new music event at Le Poisson Rouge or Galapagos, it doesn't negate the fact that there will be people interested in Melissa Dunphy that never before set foot at a contemporary new music or jazz performance (I'm guessing Rachel Maddow is one of them). How can one build a lasting audience or a 'scene' around what you are doing? Once you have an audience, how do you keep them? expand and broaden it? Does that matter? How do you connect with the audience you do have? Are creating projects such as "CNN opera", theme concerts and suites ("interview music"), gimmicky or good marketing sense in order to separate yourself from the crowd and attract audiences? Are there just too many new music groups, jazz bands, etc. out there for the market of people that want to go out for live music (and are interested in hearing new music) to absorb? Hope you can make it on the 22nd and perhaps meet some new faces for your own audience... POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 6:01 AM |

The NuminosumTo all things that create a sense of wonder and beauty that inspires and enlightens. Categories

All

|

Thanks and credit to all the original photos on this website to: David Andrako, Concrete Temple Theatre, Marcy Begian, Mark Elzey, Ed Lefkowicz, Donald Martinez, Kimberly McCollum, Geoff Ogle, Joseph C. Phillips Jr., Daniel Wolf-courtesy of Roulette, Andrew Robertson, Viscena Photography, Jennifer Kang, Carolyn Wolf, Mark Elzey, Karen Wise, Numinosito. The Numinous Changing Same album design artwork by DM Stith. The Numinous The Grey Land album design and artwork by Brock Lefferts. Contact for photo credit and information on specific images.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed