| Numinous The Music of Joseph C. Phillips Jr. |

The Numinosum Blog

|

This video came to my notice from Shadow and Act, a site that has become my recent source of what's happening from neglected and ah, darker hued participants in today's cinema and media (and one site that should be in your feed and you should be following). The Boondocks Dedicates an Episode Dissing Tyler Perry post featured a link to an episode of the eponymously titled TV show based on Aaron McGruder's groundbreaking comic strip. For years now, the strip and show has couched aspects of African-American life and culture in satirical humor and with a most observant eye. It is must viewing and reading for some insight into what's going on. If you've never checked out Boondocks, you can read some recent comics here or about learn about the show here or here. Tyler Perry, whose rags-to-billion-dollar-media-empire story is inspiring, is often criticized as trolling in and pandering to the most base stereotypes of African-Americans. The Boondocks episode is quite biting commentary on a thinly veiled Perry avatar and has sparked a reaction from Perry himself. I found the episode quite funny, go see for yourself...

POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 5:11 PM

0 Comments

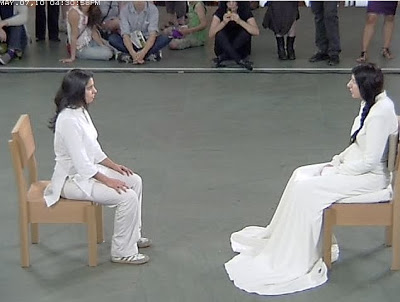

I don't remember this kind of dancing the last time I was at the New York City Ballet! Twirl was created for the NYCB's Dance with Dancers 2010 event and is a good and interesting way to promote the ballet for potential younger consumers. Of course you wouldn't want to always have something like this techno-rap, but if they could more often make the actual ballet experience as fun as this video, maybe it would really attract a...ah, more diverse, younger audience (Nutcracker excepted...). POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 8:54 AM About a month ago I was talking with Edisa Weeks about our upcoming Thomas Paine project performance in June, and she mentioned that she had just come back from MOMA's retrospective of performance artist Marina Abramovic. I had never heard of her before Edisa, and from her description I thought it would be something interesting. So I read around the 'nets about it (and some New Yorker's penchant for copping a feel of the art) and checked out the MOMA site on the retrospective, The Artist is Present. I found the interviews with Marina intriguing in documenting her growth and process of her performance art (a medium of which I'm not always on-board with).

Beyond the videos and the live nude models, I think the most fascinating part of the exhibit is the work The Artist is Present, where Marina sits in silence, from museum opening until closing (without break) in a chair opposite anyone that wants to sit with her. On the surface it seems rather un-art-like and pedestrian; what's so special about someone sitting in a chair? However, what I love is the mystery of it all. She is the unknowable watcher that is watched watching. What is she thinking or feeling? what is the other person thinking or feeling? It seems to me much like the Vipassana mediation, where you are alone with yourself mediating for extended periods. In that sense then, The Artist is Present is nothing new. However, where mediation is between you and yourself, here the meditation, while taking place individually, is also BETWEEN the two protagonists in the chairs. The art/performance itself is just a medium to express a connectivity toward our fellow beings. There's no denying that SOMETHING is happening between Marina and the other person, some communication is silently transmitted. And that's where I find it quite beautiful and moving. Just as a baby's movement or your dog's look can mean something, so to can two people sitting across from each other, have meaningful 'dialogue' with one another. I love this blog about it: Marian Abramovic Made Me Cry, which is actually funny and touching at the same time. Now I have not had the time to actually go to MOMA to see The Artist is Present firsthand (one thing I wonder is: who actually can spend the $20 admission and have the time to stand in line all day for a chance to sit with her?) but I have sometimes been checking out the Flickr photo stream (the Daily Beast said, all of those photos on Flickr are like a G-rated "still-life ChatRoulette.") as well as the performance streamed live during museum hours (although understandably, yet very annoyingly, for only a few seconds at a time before having to refresh the screen). And now, of course, something that may have had egalitarian ambitions (anyone with the hours to spend waiting in line can sit in front of her) has now, sadly and quite naturally, become a thang to do and be seen (check out the Marina Abramovic Flickr stream or MOMA's, with all of the celebs, and the regular folks too) but that doesn't take away my fascination with The Artist is Present. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 11:19 PM After listening to a report this morning about the spill coming on shore in the Gulf, I thought this tweet was apropos...

RT @dreamhampton313 @JMoneyRed @billmaher: Every asshole who ever chanted 'Drill baby drill' should report to the Gulf for cleanup duty. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 9:06 AM  I saw this sign the other day in Brooklyn and just had to take a photo. Let's hope it'll inspire better haberdasheric impulses in some young men, one of whom I passed today, near the sign, who obviously didn't look up to read it. Maybe he was looking down trying to make sure his pants were still on...Yes, people, "we are better than this!" POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 11:39 PM Wow, this recent article from The Nation, retweeted around the Twitterverse, about the undercaste of African-Americans created by the drug 'war,' brought up many thoughts. For example: Instead of attacking real issues and problems and the subsequent hard and messy work it takes to solve them, we, as a society, often grapple with the appearance of progress, the appearance of doing the right thing. What happened to "ask not what your country can do for you?" To hard work? To sacrifice? To compromise and that good ole fashion kindergarten value: sharing? To a sense of respect, of self and of the other? To a sense of 'us' not a mantra of 'whatever I can get for me and mines?' While there is much anger and distrust and despair, there is still also so much beauty and goodness and hope too. Although it is hard not to wonder that, with respect to Malcolm X's memorable line in Spike Lee's eponymous film, America is one of the best ideas humans ever had; intolerance ruined it.

POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 6:04 PM  The next Composer Salon is on Monday March 15th, 2010 from 7 pm to around 9 pm at the Brooklyn Lyceum (227 4th Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn). And the price is right: FREE! The Lyceum is literally above the Union Street M, R Train stop in Brooklyn. The Lyceum does have various inexpensive libations including different beers, wine and other non-alcoholic beverages, as well as coffee and baked goods. If you are a composer/musician in New York City area, regardless of genre, style, or inclination, I hope you can come out, meet some new and old faces behind the blogs and comments and listen or join the discussion, which often branches out from the original topic (at the end of this post are links to previous Salon topics as well as an article on NPR's A Blog Supreme about a recent Salon-don't worry, this next one will be a bit warmer than the last!). Salon Topic #5: "Music is the universal language of mankind."-Henry Wadsworth Longfellow What is communicating meaning in music? Is music's meaning defined by how it is used, borrowing an idea of Ludwig Wittgenstein? Music in a film, is film music; if it is played at Birdland or the Village Vanguard, it is jazz; if the New York Philharmonic plays it, it must be classical, etc. Or does music mean little more than sounds in time, as Igor Stravinsky writes in his An Autobiography, "I consider that music is, by its very nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all, whether a feeling, an attitude of mind, or psychological mood, a phenomenon of nature, etc….Expression has never been an inherent property of music. That is by no means the purpose of its existence." For that matter what do the labeling of music convey and mean? When someone says 'classical music' or 'jazz' (or 'anti-jazz') or alternative, what does that even mean? While many of today's composers and musicians eschew labels and genres, many others often proudly define themselves by choice: jazz composer, classical musician, rock band, rapper, etc. And when they don't define their music explicitly, their associations often betray their proclivities. Isn't one of the first questions a musician is asked when introduced to a non-musician is, well what kind of music do you write/play? Doesn't that answer affect what someone thinks about your music (and you)? Once someone knows what kind of music you write/play, accurately or not, they feel they understand it (you) and they know what it (you) means. So what does labeling one's self mean to one's music? If "music is music," as Alban Berg said to George Gershwin when Mr. 'Fascinating Rhythm' was hesitant to play piano for Mr. 'Wozzeck' on their first meeting, then why self-select a genre? Many a sensitive and creative artist wants to communicate and connect with the public. Which often translates into conveying a particular meaning to our work (whether we make that meaning explicit or not). However what happens when the listener (consumer) takes another meaning away from our work? Is this valid? Should we clarify to the public our objectives toward what the work means so as not to be misunderstood? Or should we just write and play, and let the meaning come what may. After-all, as T.S. Eliot said, “Great art can communicate before it is understood.” I. What does music mean? This evocative question was the title of Leonard Bernstein’s first televised New York Philharmonic Young People’s Concert in the late 1950’s. Fifteen years after that first concert, the third of Bernstein’s six Norton Lectures at Harvard University asked this same question. Brilliantly comparing the musical language to some of the ideas of linguistic theory, specifically Noam Chomsky’s universal and transformational grammar, Bernstein says, “Music has intrinsic meanings of its own, which are not to be confused with specific feelings or moods, and certainly not with pictorial impressions and stories. These intrinsic musical meanings are generated by a constant stream of [musical, extrinsic, and analogical] metaphors…” While not quite as rigid as Igor Stravinsky’s famous saying that music has no meaning (“music’s exclusive function is to structure the flow of time and to keep order in it”), Bernstein’s definition is similar to Aaron Copland’s position in What to Listen For in Music, “all music has an expressive power… all music has a certain meaning behind the notes… [the music] may even express a state of meaning for which there exists no adequate word in any language.” What does music express to you? What particular musical metaphors do you use to help the listener hear what you are trying to say in your compositions? What sparks the genesis of a composition for you-is it purely manipulating musical ideas, concrete extra-musical associations, and/or metaphorical expression? All of the above? II. Music, like language, is about and has always been about communication. From the performer/creator, some meaning and/or expression is transferred to the listener through, what 19th century music critic Eduard Hanslick calls “sonorous forms in motion”. Often what is transferred to the listener is not particularly definable or if it is, it is often not particularly what the performer/creator had in mind while creating the work. In the wonderful book (which I've recommended before) New Voices-American Composers Talk about their Music (Amadeus Press, 1995) Laurie Anderson speaking about communicating ideas to her audience says, “…to me the richer the image is, the better. By richer I mean clearer. It has no obstructions, it gets right across and people can understand it…I’ve chosen to be an artist and half of that, at least is in the communication of it.” She goes on later in the interview to say, “And I feel that the work has really succeeded when somebody says, ‘I saw or heard your piece and I got so many ideas from it’. Then they tell me what the ideas were, and they’ve nothing to do with what I was doing. That suggests to me that the piece was rich enough for them to take something from it and do what they wanted.” How do you insure that your compositions are clear to you? To the listener? If you feel your compositions present understandable ideas/feelings/expressions, is it successful if it conveys to the listener ideas/feelings/expressions entirely different from your original intent? Is this important to you? If you are a composer or musician or music lover in the New York City area, consider coming down to the Lyceum and joining the discussion, or if you don't live in New York or can't make it, adding your thoughts in the comments. Hope to see you on March 15th! Previous Composer Salons Composer Salon #1: The Audience Composer Salon #2: Future Past Present Composer Salon #3: Mixed Music-Stylistic Freedom in the 'aughts Composer Salon #4: Inspiration (also here's a NPR A Blog Supreme article about the Salon) (Photo credits: public domain image from the cover of the newspaper The Mascot from http://www.kimballtrombone.com/) POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 8:18 PM Whether the inmates who can't afford bail are guilty or not and whether or not corporations and unions truly have a inalienable, First Amendment right to spend whatever they want to influence elections or peddle influence regardless of the resultant effect, my question is what is happening to America's basic common sense, compassion, fairness and humanity?

POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 8:16 AM Last night I went to see director James Cameron's Avatar. I did enjoyed the film and its vertiginous use of CGI technological advancements in telling a basic (and often quite predictable, although not unenjoyable) story. And since seeing the film I have had subsequent continued contemplation of the movie's ecological message, with the obvious corollary to our own world. Despite my pleasure at the world James Cameron and crew placed on the screen, there was one aspect of the film which left me a bit disappointed: the music.

James Horner, the composer of the score to Avatar, has worked with James Cameron on a few previous films such as Aliens and of course Titanic (THE-GREAT-EST-MO-VIE-E-VER-MADE!) and he has a controversial reputation in film music circles as a recycler of his own themes and motifs as well as some say a, ahem, 'borrower', of themes and motifs from other composers (in Avatar, I notice a few obvious moments of recycled Horner, such as a snare motif borrowed from 1986's Aliens which in itself, was also used in 1982's Star Trek 2: The Wrath of Khan). Avatar's music is generally pleasant and serves the film's visuals passably as the sound world James Horner creates certainly having elements from what we've come to expect from blockbuster film music. For example, rousing and rhythmic battle scene music to accompany the hordes of CGI warriors (with a parallel to Howard Shore's score to The Lord of the Rings), an exotic sounding choir matched with ethnic percussion (similar to Ennio Morricone's music to The Mission, with nods to Horner's own Titanic), and the requisite 'hit song' during the closing credits and which, not always but often, seem out of place and jarring, as it did in Avatar (think the song at the end of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon or "My Heart Will Go On" at the end of THE-GREAT-EST-MO-VIE-E-VER-MADE). But in many ways the music is an antipode to the visual technological innovations. Why do directors, who claim to be breaking boundaries in their films, fall back on using standard movie music memes? In Avatar, sadly there is no musicological equivalent for the stunning visual world saturated with beautiful dendrological, entomological, botanical, zoological, and geological interest and imagination (most things are based on recognizable earthly models such as a glowing forest floor, the 'helicopter' lizard, the white butterfly-like seed from the sacred tree which looked like a cross between a jellyfish and a dandelion seed head, and the Hallelujah Mountains (which all during the film I was speculating on how they would be able to float, perhaps some kind of terrestrial variation on Lagrangian points)). And while there is not much source music in the movie (music that emerges from a source in and from the world on-screen, as opposed to the music score, which is strictly outside it), the few times there were, particularly a scene toward the end where the entire Na'vi tribe chants, musically it was fairly straight-forward and plain. Now this is not to say the music doesn't help the visual images, but if James Cameron's team were able to create such a visually striking alien people, with their own legends and spoken language which was commissioned for the film, why couldn't there also be some hint of an equally imaginative, forward-sounding music, if not in the score at least in those moments in the film when the aliens are actually singing? Maybe I'm a bit unfair since my criticism stems from what James Horner (and James Cameron) did NOT do and what the music is NOT. After all Star Wars was looking back, not forward with its pseudo-Wagnerian romanticism including its one source material moment, the Cantina Band and its galactic-steel-drum electro-swing. However, where John Williams created a great and memorable score for Star Wars which was in the vanguard of helping popularize a return to big, sweeping 'operatic' orchestral music in movies (after a decline in the 1960s and early 1970s due to more pop music being used), James Horner only creates a decent, functional, and prosaic score. And for a film as 'next generation' as the moving-graphic-novel Avatar, that is disappointing. (Photos from the official Avatar website) POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 11:15 PM Last week ended Maximum Reich, WQXR's radio fest of the music of composer Steve Reich. Hearing much of what Reich wrote over the past 40-45 years, it is hard now to describe how revolutionary his music from the late 1960s and early 1970s was. How refreshing and influential works such as Come Out, It's Gonna Rain, Piano Phase, Drumming, and of course Music for 18 Musicians were, not only on young composers and musicians but also on the listeners, who were treated to music that defied categories of classical by melding it with rock, jazz, and music from other cultures around the world into a decidedly American conception of what music could be, what I call mixed music (music consciously borrowing influences into something that is completely different from the source materials--I could argue that jazz, really was an early form of mixed music though).

Of course Steve Reich did not stop making music after those early works from the 60s and 70s. Some of his later worksDifferent Trains, Electric Counterpoint, Desert Music, Tehillim, Three Tales, and his Pulitzer Prize winning Double Sextet, expanded upon his technique and shows that he still has much that is worthwhile and interesting to say musically. However, after hearing most of the Reich output on WQXR, one question came to mind: does he write the same piece over and over? Hearing works such as his new Mallet Quartet along side Sextet or Daniel Variations along with You Are (Variations), one could make the argument that generally many of his works, particularly the later ones, do sound similar, at least on a superficial sound world level: mallet instruments and keyboards playing short repeating rhythmic cells that are layered and varying; if vocals are added, there is sometimes a juicy astringent, dissonant quality as the voicings sometimes feature close harmonies between voices, often doubled with the wind instruments; a dense texture of multiple sounds with a general energetic forward propulsion of motion. In 2003 I was part of the Steve Reich Festival in the Netherlands, where a number of seminars and symposiums were given, along with many performances of his work, in which Reich spoke about his influences, process, compositions, and philosophy of writing music. I remember one session I attended, where he was saying that he gets some criticism for writing works that "sound the same". He laughed and then asked us in the audience if we thought that was true. Now of course, no one, especially if they were thinking yes, were going to answer him right then and there. Anyway, he went on to talk about whatever it was he was discussing before that question, and the subject of writing the same piece over and over didn't come up again. And frankly, until the moment he posed the question, I hadn't really given a thought whether his works sounded the same. I just enjoyed each piece of his for what it was. However, I've been thinking about that question off and on ever since that day. Or more precisely, I've been thinking what should be a goal of any composer? Is a composer's goal the refinement and distillation of a particular language and sound, with each subsequent piece an expansion of said language, sound and technique or should a composer's language and sound change from piece to piece, with no definable connection between pieces except that the composer wrote it? This has some relation to the last Composer Salon topic, Mixed Music and Stylistic Freedom, where I discuss this concept further, but it gets to the heart of what composer Daniel Lentz means when he said in an interview, “style is really just learning how to repeat yourself, sometimes endlessly. If you keep changing your language and what you do, which is a very noble thing to do, nobody will know who you are?” If a composition (or any work of art) is some representative of a composer's (or artist's) being, then can one create beyond what and who they are? After all, in Steve Reich's case, he is who he is, should he (or could he) ignore who he is and create something that doesn't sound like Steve Reich? In Western art and literature, even during the rise of Romanticism in the 19th century, which prided itself on individual expression, an artist's work was still part of a recognizable personal oeuvre. It has only been recently (20th century?), partly due to the many more sources of inspiration readily available to us than in previous epochs, that eclecticism of personal style became so prevalent. Pianist and writer Charles Rosen wrote in his book The Classical Style, “What makes the history of music, or of any art, particularly troublesome is that what is most exceptional, not what is most usual, has often the greatest claim on our interest. Even within the work of one artist, it is not his usual procedure that characterizes his personal ‘style’, but his greatest and most individual success.” In musics from other cultures, the idea wasn't to be so individual as to become unintelligible to listeners. From India to Arabia and Persia one gained esteem and acclaim, not on eclecticism but on how well you adhered to a particular style, yet still able to add something individual to that style (in this regards, it reminds me much of the true spirit of jazz). Generally the practice could be described by the famous saying of Goethe, "In der Beschränkung zeigt sich erst der Meister (In limitation, the master reveals himself)." So the relevant question for this post about Steve Reich's music is, does it sound the same from piece to piece? Does it matter? And if so, is that a function of the refinement over the years of his sound, a variation of the same theme so to speak, or is it just that it is easier to write how and what you already know and harder to find some other way to say what you need to say? Or should you? I think about authors and whether this question is the same for them? Does Jhumpa Lahiri get accused of writing the same story over and over again when her subjects are mostly Indian/Bangladeshi or immigrants from there? Does Toni Morrison, because she writes about African-Americans? When you read a Steve King novel, you know you are reading a Steve King novel, should he write like Philip Roth? Maybe this isn't a true equivalent, but I do wonder if this problem, really is a problem at all. What any composer would want, I think, is to have a readily identifiable sound or style, which would mark it as theirs. While there might be some similarities in language and technique, can't one tell the stylistic differences between Debussy and Ravel, Brahms and Dvorak, Coltrane and Sonny Rollins, Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye, Beyonce and Mariah Carey? So what is that thing that identifies each artist as distinct? Did they get criticized for writing or performing the same piece or same style over and over? Ultimately though, each artist has to come to grips with the larger personal question of how to balance learning to repeat one's style and language with an exploration of new approaches and techniques, in order to express that which needs to be expressed with one's art or music. And in this regard and in finding the answers for himself, I think there is nothing wrong with being Steve Reich. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 10:00 PM  This past Wednesday night, December 9th, I went to hear composer/saxophonist Matana Roberts perform her COIN COIN project at the Issue Project Room in Brooklyn. The project is wonderfully hard to classify, as it is a fountainhead drawing from multiple streams of influences, but Matana describes it as, "...a large scale 12 segmented sound narrative about my family history [called COIN COIN]. Through research, interviews and loads of family help, I have been able to explore stories, folklore, and mystery surrounding my ancestral history going back to about 1704, covering at least 3 continents, spanning a ridiculous cross section of cultures..." Coin-Coin was a legendary figure in some mid-18th and 19th century southern African-American lore, but she was a real person: Marie Thérèse Metoyer, a women (and possible ancestor of Matana) born a slave in Louisiana but through various circumstances, became a free women who ended up a successful landowner, slave-owner, and businesswoman at a time when most blacks (men and especially women) were illiterate, uneducated, and poor. Matana maintains a blog, In the Midst of Memory detailing her thought process on different subjects dealing with developingCOIN COIN and you can find out more there, as well as links to interviews discussing the project. On Wednesday night as I listened, I was reminded of a surface tonal connection between COIN COINand Cormac McCarthy's The Road (which I read a couple of years ago and saw the movie over Thanksgiving weekend). Both have a topical seriousness and desolation in which laughter, joy, or hope seemly is an ancient legend people only could vaguely comprehend. Of course this is to be expected dealing with the horrors and terrors both are dealing with. However after thinking about it more, The Road comparison is only partly accurate and COIN COIN, underneath the surface, probably has more cultural resonance with some other books I've read: The Known World by Edward P. Jones, Toni Morrison's Beloved or A mercy, and Jeffrey Lent's In the Fall. Those powerful and solemn books deal with issues in and around slavery and illuminates the psychic and psychological toll inflicted on all involved and all who survive (both black and white). Each book has a surface theme one could describe, as one character in In the Fall says, "Mostly, people are cruel, given the chance." Now I do believe everyone, given the right circumstances, has the capacity to live up to such a negative statement, however I don't subscribe to that pessimistic view in the reality of day-to-day. I am an optimist but with such depravity in history, it does make one empathetic to the felo-de-se of some who are oppressed and who lack opportunity through no fault of their own. Yet, despite that stream of anguish, one comes away from each book (well, at least me), not with lack of hope or with despair, but with an astonishment at how one can go on and how one does go on when faced with such abjection. How much would you cost? is one of the questions Matana asks in COIN COIN and which I believe she means what is one's own value as a person (both the literal monetary question referenced in slavery but also solipsistically as who one is) but I think another way to think of it is, what would you do or what would you be, placed in a similar horrific situation or circumstance? Would you have the same desire to survive, to continue? Would you degenerate to cruelty and self-destruction or as The Kid says in the movie The Road, would you still be a "good guy?" Leonard Bernstein said it well in his fifth Harvard University Norton Lecture from the early 1970s, The Twentieth Century Crisis, "Why are we still here, struggling to go on? We are now face to face with the truly Ultimate Ambiguity which is the human spirit. This is the most fascinating ambiguity of all: that as each of us grows up, the mark of our maturity is that we accept our mortality; and yet we persist in our search for immortality. We may believe it's all transient, even that it's all over; yet we believe a future. We believe. We emerge from a cinema after three hours of the most abject degeneracy in a film such as La Dolce Vita, and we emerge on wings, from the sheer creativity of it; we can fly on, to a future. And the same is true after witnessing the hopelessness of Godot in the theater, or after the aggressive violence of The Rite of Spring in the concert hall...There must be something in us, and in me, that makes me want to continue; and to teach is to believe in continuing. To share with you critical feelings about the past, to try to describe and assess the present--these actions by their very nature imply a firm belief in a future." Now while I positively enjoyed both COIN COIN and The Road, I didn't feel like I 'flew away' after reading or after seeing it. However, I did feel that desire of humanity to survive, to live, to keep moving on. COIN COIN struck me as sonic consonance of the themes and feelings to be found in books like The Known World. The compositions were often structured improvisations mixed with definite written sections for the ensemble. Sometimes during the performance there was a box passed between the musicians, with color-coded beads inside, which corresponded to color-codes on the musician's parts and determined how they navigated the written music (Nate Chinen, who conducted a post-concert talk with Matana, has some photos of Matana's music here). The music flowed seamlessly from piece to piece for about an hour and a half and was a polyglot of stylistic diversity. Sections of contemporary classical gestures mingled with free jazz, spoken word, and modal jazz (a la mid-1960s John Coltrane, think the Impulse albums Crescent or Coltrane and you get an idea), performed by a wonderful ensemble (Gabriel Gurrerio (piano) and Daniel Levin (cello) stood out, but also featured were Jessica Pavone (viola), Keith Witty (bass), and Tomas Fujiwara (drums)) lead by Matana's sinewy alto saxophone playing and sometimes her speaking, singing, scat-rapping, and on three occasions, issuing a primal, tortured scream, which seemed to emerge from the depths of the spirits of all of her black ancestors. A powerful accompaniment and counterpoint to the music were video projections by Daniel Givens early in the evening but especially later when photos from Matana's family lineage, dating from the late 1800's onward, were shown behind the band. Like most African-Americans today, Matana's family comes in many different hues and shades of black, brown, and white. Seeing the photos of marriages, parties, school photos, celebrations, one had a pride and joy at seeing middle-class African-Americans in the early 20th century, so often seen by history in such stereotypical distress and poverty, being depicted in all manner of complexity in life: with dreams, and loves, and desires, and faults just like anyone else. Of course watching the photos, I couldn't help thinking about my own family history and how I fit into it as well as the larger African-American tapestry, even though that tapestry is only one part of many elements defining who I am. And I think this is one thing that is intriguing and universal about COIN COIN, no matter your 'race': through Matana's exploration of her own history, it helps open up your awareness to connections to your own family past and to one's inner self reflection of what that means to who you are. Seeing such an unclassifiable project, one that mixed dramaturgy, sociological and anthropological research and study, performance art, and jazz, one could trace influence to some past projects from the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), of which Matana, from her own admission is a tangential member (if Chicago's Second City is the incubator of much of American comedy today, then AACM has to be some kind of equivalent for the downtown music scene all over the globe). But Matana's work is singular in its own ambition and powerfully thought-provoking in its scope. I, for one, am happy to know of her work and that she addresses such a subject with clarity, questioning insight and vision and I look forward to seeing COIN COIN develop in the future. It is a project which should be seen and heard and discussed by many more. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 1:00 PM On Wednesday I responded (twice) to a posting on Greg Sandow's blog entitled Labels. The posting was (I thought) a discussion on what to call the sort of new music found in contemporary classical music circles that draws as much inspiration from Radiohead as Stravinsky. Greg Sandow and others call this kind of music 'alt-classical' while some call it post-classical. In my response to the post, I offered an alternative term, mixed music, to describe this cross-genre music not just in classical music but in other genres as well. Unfortunately (and surprisingly), you will not find my comment on Sandow's blog. Not sure why my response and suggestion wasn't published (is it not as valid and descriptive as alt-classical?) but you can judge for yourself the merits of the term mixed music versus Sandow's alt-classical. Here's what I wrote:

Greg, this whole thought about labels was running through my head during a vocal concert of various 'alt-classical' composers last week at Galapagos. I've been thinking about this for awhile now (well before last week) and it actually inspired the topic for my next Composer Salon as well as a possible alternative to the phrase alt-classical (which while fine, as Chris [Becker] points out above, it seems to be talking about a specific number of young, educated, well-connected NYC composers and so a bit limited and which Molly [Sheridan] points out seems to be a tired hipster marketing attempt to describe the aforementioned type of composer (and their audience) in analogue to the alternative rock world). My term mixed music is borrowed from the racial usage of being of mixed heritage and you can read some of my reasoning to use it to describe today's music at my blog. But in general I think mixed music can be used in a broader sense to describe much of today's cross-genre musical ruminations in classical, jazz, and even pop/rock and beyond. Yet I fully recognize that any label will not be sufficient in capturing accurately all of the 'scenes' or ideas therein and doesn't really say what the music actually sounds like, but I think it works as a description of the general trend today. Also you can check out the link to the next Composer Salon where I discuss mixed music in more detail. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 6:00 AM  It's time again for the next Composer Salon on Tuesday December 8, 2009 from 7 pm to around 9 pm at the Brooklyn Lyceum (227 4th Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn). The Lyceum is literally above the Union Street M, R Train stop in Brooklyn. The Lyceum does have various inexpensive libations including different beers, wine and other non-alcoholic beverages, as well as coffee and baked goods. If you are a composer/musician in New York City area, regardless of genre, style, or inclination, I hope you can come out, meet some new and old faces behind the blogs and comments and listen or join the discussion. Salon Topic #3: “What makes the history of music, or of any art, particularly troublesome is that what is most exceptional, not what is most usual, has often the greatest claim on our interest. Even within the work of one artist, it is not his usual procedure that characterizes his personal ‘style’, but his greatest and most individual success.”—Charles Rosen, The Classical Style On November 19th, I attended the 21cLiederabend concert at Galapagos Art Space in Brooklyn's fashionable neighborhood of DUMBO. The performance, co-produced by Galapagos, VisionIntoArt, Opera on Tap, and Beth Morrison Projects, was billed as "a multimedia performance featuring vocal works by some of New York's rising young stars of post-classical composition." Composers Caleb Burhans, Leah Coloff, Corey Dargel, Osvaldo Golijov, Judd Greenstein, Ted Hearne, David T. Little, Missy Mazzoli, Nico Muhly, Milica Paranosic, Kamala Sankaram, and Paola Prestini all had pieces performed and while I enjoyed most of the compositions (some quite a lot: Greenstein's "Hillula", Golijov's "Lua Descolorida", and Mazzoli's "Song from the Uproar" were three of my favorites) at some point during the show, as I listened to the works brimming with compelling ideas and sounds, I began to wonder what music historians will make of our age. Almost all of the compositions had a seriousness purpose, to be expected from the erudite and aware composers. Happily, for me anyway, while there wasn't any real stylistic unity between the compositions, there were a few things in common. One was that each composition seemed to be intent on working a 'new beauty' aesthetic: generally euphonic sounds (even the dissonances) with a more contemplative (not necessarily slow) musical tone. Second was that all of the pieces seemed to be what I call, mixed music: music that goes beyond the rigid definitions of a singular genre to organically fuse multiple styles into something completely different (think how children of mixed race couples are neither one yet both of the races of their parents). For example, the compositions at Galapagos were clearly influenced in form, instrumentation, and rhythmic and harmonic adventurousness by classical music but also included elements from other more popular musical forms and cultural sensibilities (whether pop, rock, hip-hop, etc.). Other terms for this type of composition in the classical world are alt-classical or post-classical, but I think my term mixed musicbest describes this trend in music because it can reflect many different hybrids of styles: from the jazz world (groups such as the Bad Plus and Darcy Argue's Secret Society mixing the jazz and rock/alternative worlds; Robert Glasper's work with Q-Tip, Kanye West, Mos Def, and Maxwell or Roy Hargrove playing with D'angelo or most of MeShell Ndegeocello's output all working the jazz and creative black popular music angle (sometimes with a decidedly Prince-ian eclecticism and élan); contemporary classical and pop or electronica (Nico Muhly or the new In C Remixed recording) or my own compositions with Numinous, which fuses elements from contemporary classical and jazz to other more popular forms). While there is much fundamentalism and narrow-mindedness in values and taste in today's society, which is often defended in the most obstreperous manner leading to more and more ossification of those values and tastes (think of the political climate in the US and you get what I'm saying), I could argue that this entire generation or era is one of mixed sensibilities: racially, financially, temporally, and culturally. Even though I'm not one for labels since they usually only hint at something and are partially accurate at best, I do understand in the 'real world' that they are necessary so the term mixed music seems an appropriate one to describe much of the music of our time, at least in much of the creative artistic music with its heterodox movement toward a 'beyond-genre-ness'. But there is a danger with no overarching stylistic unity or this blending of styles and influences to center or ground a composer, similar to what Leonard Bernstein discussed about music's meaning and intelligibility in his Norton Lecture "The Delights and Dangers of Ambiguity": what makes a composer's voice consistent and understandable from piece to piece? At the 21cLiederabend concert I was reminded of Wassily Kandinsky’s discussion of Pablo Picasso's style in his Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Of Concerning the Spiritual in Art). Speaking of Picasso he writes: “Tossed hither and thither by the need for self-expression, Picasso hurries from one manner to another. At times a great gulf appears between consecutive manners, because Picasso leaps boldly and is found continually by his bewildered crowd of followers standing at a point very different from that at which they saw him last. No sooner do they think that they have reached him again than he has changed once more.” With all of the stylistic borrowing, how do you make something that isn't pastiche? What filament runs through someone like Picasso to make it Picasso? I mean Steve Reich sounds like Steve Reich. John Adams, John Adams. Philip Glass, Glass. Charlie Parker. Bird (well, I guess you could say Sonny Stitt also sounds similar to Bird, but that's another discussion; on the Jazz Loft Project Episode #10 listen to pianist Paul Bley talking about finding one's own sound after Charlie Parker died). But listening to the composer's compositions on November 19th, what thread runs through their works? Besides their names on the scores, what makes a piece by Missy Mazzoli, Missy Mazzoli's? Nico Muhly, Nico Muhly's? Joe Phillips, mine? And, of those on the Galapagos concert, asking the question Norman Lebrecht asked in his recent poll of composers we'll still be listening to 50 years from now, whose sound and music will we be hearing from 50 years from now? 100 years? 10 years? Does it really matter? To relate to the Charles Rosen quote above, is all of this stylistic borrowing and the music that encompasses it, what is 'exceptional' in our age or usual? Years from now, what will mark people's interest in the music of now? So here are a few thought-provoking statements and fodder for discussion relating to style and the freedoms (and limitations) in our mixed musicera: I. Arnold Schoenberg writes in his Die Musik, “Every combination of notes, every advance is possible, but I am beginning to feel that there are also definite rules and conditions which incline me to the use of this or that dissonance.” What are the rules now? Is it rules or just taste? Whose taste dictates what is 'good'? II. Jazz composer, pianist, and AACM founding father Muhal Richard Abrams tells Francis Davis in a February 1991 article, “In the beginning, jazz was an abstract process. It wasn’t any particular style yet. It sounded like whatever the musician wanted it to sound like. It stood for the freedom to experiment, the excitement of things never quite coming out the same.” Do you feel jazz has moved away from the inclusive origins Abrams talks about? Is that spirit and 'freedom to experiment' alive in today’s jazz? How do you balance experimentation with standard practice in your own music? If it sounds like 'whatever you want it to sound like' why identify yourself as a 'jazz' composer? a classical composer? a pop musician? etc. III. Composer Daniel Lentz says, “style is really just learning how to repeat yourself, sometimes endlessly. If you keep changing your language and what you do, which is a very noble thing to do, nobody will know who you are?” Do you agree with this statement or not? Thinking about the Kandinsky quote on Picasso, do you strive for a “coherence or singularity” in your musical language or is your language "tossed hither and dither"? What characteristics would define your own personal style? IV. Morton Feldman writes in his essay "The Anxiety of Art", “The painter achieves mastery by allowing what he is doing to be itself. In a way he must step aside in order to be in control. The composer is just learning to do this. He is just beginning to learn that controls can be thought of as nothing more than accepted practice.” Is control nothing more than “accepted practice”? How do you control and manage the flow and freedom of ideas during the composing process? How does this relate to the Daniel Lentz quote above? If you are a composer or musician or music lover in the New York City area, consider coming down to the Lyceum and joining the discussion, or at the very least adding your thoughts in the comments. Hope to see you on December 8th! POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 5:19 PM Here is an insightful article about how the words of America's 'lost founding father' Thomas Paine find themselves in Sarah Palin's new book, Going Rogue. The article's author is historian and Paine scholar Harvey Kaye, whose book Thomas Paine and the Promise of America (which you should read by the way) along with, of course, the actual writings of Paine, was one of the catalyst and inspirations to my dance project in June 2010 with choreographer Edisa Weeks, To Begin the World Over Again. The article cogently argues that Palin along with other conservative politicians and thinkers wrongly decouple Paine's words with the actual radical and progressive thoughts behind them.

POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 7:20 PM I just saw the November 16th issue of New York magazine with the cover story entitled, Brooklyn's Sonic Boom: how New York became America's music capital again.

The cover photo shows three 'indie' rock bands (does indie mean anything anymore if almost everyone seems to be independent now?): Dirty Projectors (the photo above, from New York Magazine), Grizzly Bear, and MGMT. Honestly, the first thing I noticed is that everyone in each photo has the same hipster, non-smile, smile: Mona Lisa-esque pursed lips and the eyes either a 'cool-young-rock-band' stare, a faux-self-deprecating laughing irony, or a hipster distance. Second thing I noticed, as I opened the magazine to read the article, was a glaring dearth of diversity. Not just racial, which is pretty obvious, but also musically. Really, Brooklyn doesn't have a vibrant hip hop and rap scene? how about jazz? a happening black rock scene? With an article that purports to show how New York is "America's Music Capital" again, shouldn't there be a cross-section of musical happenings in Brooklyn now? Or you if you wanted to keep the article's same focus, you could have a title with less rhetorical flourish and which reflects more truth: Brooklyn is the Music Capital for those parts of America that like independent rock music made by young-ish, (mostly) white, educated people. How many times do we need to keep hearing about the young, Williamsburg hipster indie rocker (and this isn't criticizing the music by these groups, which I've checked out some of, and like some of; just the coverage)? I get it. Young. Cool. Hip. Attractive. Good Music. Of course this kind of coverage is the same in the classical music world, with the young-ish new music-y types. Please guys, next time can we go a little farther afield than Williamsburg to find out what is really happening musically in Brooklyn? POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 1:13 PM Over at Greg Sandow's blog one of his reader's named Janis has a wonderfully intriguing idea inspired by the Star Wars Uncut website.

Here's the idea as Janis describes it: Take a well-known shortish piece of music (not an obscure one, one that a lot of people know, like a nice standalone piece of Beethoven's 9th or the end of the William Tell overture), and break it up into bits, perhaps twelve measures apiece. Open them up to being "claimed" by people online, probably students. Each student claims a chunk of the music ... and interprets it however they want. Some will play it straight on an oboe or violin. Others may whistle it. Others will use synths, others can hum it, still others can bang on kitchen pots. They upload their "chunks." Then ... stitch the pieces together and play it. Some of my thoughts about the idea for classical music, are over in the comments at Greg's blog, but here's a point I said there and I'll repeat here: SW [Star Wars] is quite iconic, even the causal moviegoer or non-sci-fi fan, knows SW. While the Beethoven and Rossini examples are quite known, I don't think they rise to the same level of coverage in the general public's consciousness as SW. And sure the people who are doing the SW send-ups are probably SW fanatics, but the people who view it are, my guess, more broad than that since the movie goes beyond sci-fi fans. I don't think you'd ever get the same broad cross-section of listeners with a classical music version. As an idea for classical music fans, I think it is great and a very fun thing to try. Heck, I might even try my hand at one little chuck of Beethoven if the idea becomes reality. But part of the idea reminds me of various responses (rebukes?) of some of the ways artists today have to keep coming up with more and different 'pitches', just to be heard over the din of societal "overchoice". Really?!, how relevant can classical music (or jazz or any art, for that matter) be in today's world, if the only way to get the layperson to listen to or see your work is to create a Rossini mix contest or a YouTube Symphony? or put a shark in formaldehyde? (or, in a completely different vein, to hide your son in the attic in hopes of a reality show? or yell "You Lie!") Are these truly the ways to create a lasting connoisseur of one's work or position in today's world? Artists, musicians, actors, writers and other creative types (not to mention politicians) always had to be imaginative barkers when marketing themselves and their image to the public. As Jacques Barzan wrote in The Use and Abuse of Art, "Historically, the artist has been a slave, an unregarded wage earner, a courtier, clown and sycophant, a domestic, finally an unknown citizen trying to arrest the attention of a huge anonymous mass public and compel it to learn his name." And I'm not knocking people for trying these different ways to be heard; it is actually fun to come up with meaningful and real avenues to connect listeners with one's artistic product. I'm just wondering why it seems so much harder these days? what has changed to make it so? Anyway, check out The Star Wars Uncut site if you haven't, it is pretty fun seeing what people have done with their scene and it reminds me of some of the continued voyages of fans in the Star Trek universe. Not that I have seen those...really, I haven't...really... POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 10:10 PM This past weekend I was listening with interest to a story on NPR about middle class black and Latino students and the continued achievement gap with their white and Asian peers of similar backgrounds. Part one was on Weekend Edition Saturday and part two on Sunday. The NPR site also has a link to the full hour long radio documentary, Mind the Gap: Why Good Schools are Failing Black Students by Nancy Soloman as well as a few links to other related stories.

I'm still processing how I feel about the story and my own thoughts about the gap, but among many things, I found this interesting from the story: [Melissa Cooper, sociology teacher at Columbia High School says] racial stereotypes are so powerful that black children are much more limited in how they see themselves, even in a place like Maplewood [NJ], which is largely middle-class. "It's a freedom that white children have that black children don't have," she says. "They get to pick from this huge array of personality types, behaviors, authentic selves that they can put on and take off. There is a challenge for black children in terms of, when they go to the identity closet, how may options of what guise they can put on and take off, and still be considered authentically black." This question of black teenagers and their identity is a clue to the mystery of why middle-class black students aren't keeping pace with white and Asian students. Middle-class black students do just as well as their white peers in elementary school, but as they become teenagers, they begin to fall behind. Pedro Noguera, sociology of education professor at New York University, says middle-class black children have the same benefits of middle-class white children— two parents at home, lots of support and extracurricular activities — but many of them desire to be more like poor children. "In many black communities, it is the ethos, the style, the orientation of poor black kids that influences middle-class black kids in ways that [are not] true for middle-class white kids," Noguera says. "Most middle-class white kids don't know poor white kids. I do feel that that is true to some extent. Impressions and images of African-Americans and Latinos are often limited to a few standard tropes in many minds and especially in the media (in music, I think of how far away "black rock" or country music seems from the mainstream view of what is black or even light years away from that, African-Americans in the classical world). And while I do wonder when the media will show the complexity and range of the black community (see "DORF" post October 2009), I also wonder with all of the opportunity of wealth and education offered to some of the young middle class African-Americans in the story, when does it become THEIR responsibility to defy the challenges of stereotype? of wanting to be more than a rapper, sports star, or entertainer (not that there's anything wrong with that, of course)? of not wanting to only sit in the middle of the classroom and "never so much as pick up a pencil, and often disrupt the class"? beyond all of the external societal issues, a case could be made for why are some black students failing themselves? POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 9:40 AM One year ago, on November 4th, 2008, was the historical election that seemed to bring in that air from another planet. Even though there were no students that day, we still had to be at school for professional development. On my way to work you knew something was different about this election as people were lining up around schools and churches to vote. About 8:30 am that morning as I arrived to the work, there was a long line of people down the block, snaking around my own school and filing inside in order to vote. There were smiles and happiness of purpose on the faces; an anticipation of something happening (or about to happen) and that they were part of it. Of course this being Park Slope there weren't many brown and black faces, but there were some in that line. But what I loved seeing were parents who brought their kids to the voting booth. To give the young that experience which hopefully will carry over to their adulthood was very heartwarming. There was such a palatable excitement, I felt that people finally were fulfilling the "promise of America" that author Harvey Kaye wrote about in his exciting book on Thomas Paine (that book is one of the influences to my upcoming dance project). Not that America is perfect but it is the potential of America, as an idea, as an ideal, to be so much more than those countries of history with their kleptocratic, monarchical, dictatorial, plutocractic, and culocratic ways; that the people are the government and could be in charge of themselves seemed such a radical, revolutionary concept (reading about the history of the American Revolution, it is even more amazing that things could have turned out so differently for America). And despite the many assaults and challenges over our history that promise, sometimes bruised and shaky, is amazingly STILL there. Of course the solutions to our country's many problems aren't easy. They never were and never will be. And with all of the noise of anger and frustration out there that things are moving too fast or too slow or too much or too little, the answers will be even harder to find and agree to. Whether you are black, white, Democrat or Republican, agree with the economic bailouts and the war or not, for big government or little, love FOX or love MSNBC, or somewhere in the middle, last year's election meant something greater than just the election of the first (half) black President (and with the racial history of this country that election DOES mean a lot). Rather it was because people actually seemed to CARE about the future of the country and more importantly, DID something about it. Just after the election last year my wife heard on our Brooklyn street a conversation of two young African-American men walking down the sidewalk. Both were talking about the election results and were obviously excited. She overheard one say to the other something like, "well now I need to pull my pants up." I think if last year's election can help one young man realize that falling pants is not cultural statement, then something magical happened last year and no matter your political persuasion or affiliation, we should all celebrate that. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 8:00 AM Just came across this interesting opinion article from Slate about the lack of "all" in NPR's All Music Considered. The idea in the Slate article that indie-rockers are THE most valued by NPR and their listeners, all of whom share similar backgrounds, and are most like them (and who are more often than not, the gatekeepers of cultural taste and history) hits at the perception game I talked about in a post this summer.

"Maybe a problem is how those [African-American] musicians are valued or perceived both in the general and black public and press, not on the quality of their work. An on-going dialogue 'Ain't But a Few of Us: Black Jazz Writers Tell Their Story at The Independent Ear discusses the lack of coverage of black serious music by even the mainstream black press but I think it also focuses a light on what all press in general deem important, worth covering or probably more accurately, what the editors believe the readers want to read...With choice of what is covered denotes the perception of "importance" or "worthiness" and I think writer John Murph put it cogently for some African-American musicians in an interview on The Independent Ear when he says, "...there’s the whole idea of what is deemed more artistically valid when it comes to jazz artists incorporating contemporary pop music. I notice a certain disdain when some black jazz artists channel R&B, funk, and hip-hop, while their white contemporaries get kudos for giving makeovers to the likes of Radiohead, Nick Drake, and Bjork." And later I go on to write, "And whether something is perceived as quality hits on the head what I think because since the majority of tastemakers, gatekeepers, mavens are not black (or women), and often come from different socio-economic and educational backgrounds and experiences, maybe sometimes African-American musicians (or women) might not be as fully understood, valued, or appreciated as someone coming from the same background." When you think about the inroads that rap and hip-hop and other 'urban' music has had on the Top 40, why isn't music from non-DORF artists not shown the same acclaim and accord as their indie-rock brethren? In a more recent post (September 2009) where I'm talking about jazz music's 'too cool for school' perception, it could equally be attached to non-DORF artists of color. "While today much of urban or black and Latino culture and music is fairly mainstream, the power or control in what people see, hear, and for the most part do, is not in the hands of minorities. A small group of tastemakers and insiders lets us know what is cool by what is covered, advertised, or showed [in the mainstream]. How many minorities are part of this group? Not many. Why?" This a problem in many parts of the mainstream society. While the typical NPR listener might love an indy movie such as The Education, my guess is that many (certainly not all) would shy away from something like Precious, which while certainly worthy of critical attention, might be perceived as being 'too black' or 'too urban' by many. And hence not seen with the same quality as something with more Anglo sensibilities. Or while I might not personally like many of Tyler Perry's movies, the lack of coverage about and the respect toward his quite financially successful production studio operating outside the standard Hollywood machine, seems quite strange for a culture that loves a good "Horatio Alger" myth. Or more importantly, how a majority African-American or Latino school (or neighborhood) might be looked at with inferiority or condensation by some, no matter how successful and/or affluent they may be. Or the thought of how during last year's election, some said Obama couldn't show anger at all of the false accusations from the GOP because he would be perceived as the "angry black man" and this would have (supposedly) scared or killed off many of the white, liberal voters. I mean, c'mon, if I'm angry at unjust or unfair criticisms, I should be able to show it, just like anyone else, without feeling like I'll be dismissed as a classic stereotype. All of these are examples of how a certain bias might be ingrained in what we see as quality or valuable or relevant. Hey, I'm a regular NPR listener and have been a member too (WNYC!!!) and frankly, it doesn't matter to me too much what music NPR programs and which musicians are profiled (as long as it is good), as the Slate article states, "in matters of musical taste, everyone has a God-given right to provincialism and conservatism, even those NPR listeners who consider themselves cosmopolitan and liberal." (Maybe the DORF aesthetic is like what Chris Rock said in his new film, Good Hair, about how "relaxing black hair relaxes white people": maybe DORF programming relaxes NPR listeners?). But it DOES matter to me whether a minority artist or musician, who might be foreign to the tastemaker's cultural background (or to their usual social and professional circles), is perceived as less worthy of acclaim, not because of their music's worth, but just because they aren't understood as well. POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 3:04 PM Last week I read the Daily Beast article, "America's New Racial Reality" about what is happening in the so called post-racial era of Barack Obama. I was reminded of that article as I read the comments section of a post a few days ago by Matt at Twenty Dollars, "Just Make Us Look Cool", in which Vijay Iyer writes,

"so you seem to be highlighting this phenomenon wherein white people wield the privilege and power to insult the disempowered, underfunded genre of jazz in all-white, multimillion-dollar hollywood films and tv shows (thereby empowering millions of mostly white viewers to do the same); to gleefully flaunt their own ignorance and hatred of this music; and to revel in the degradation of people who know or care about it. this suggests to me that maybe this “coolness” problem is really about the freedom of white americans to publicly loathe jazz. maybe the music is a reminder of black american achievement and therefore of white guilt, so it is just easier and more satisfying for white americans to categorically, if unconsciously, reject it." Jeff Brock, also in the comments, counters with, "To categorize the rejection of “jazz” as an act of “white america” is silly" and goes on with, "After all, 'jazz' audiences are predominantly white." While I do agree with much of what Jeff goes on to say about the topic of why jazz isn't "cool" and more widely embraced in the wider world (not going to get into the discussion about what is jazz, which is another can of worms), frankly I don't find the possibility of some subconscious sub rosa bias "silly" at all. It isn't what is fully going on with the rejection of jazz, but that doesn't dismiss it as an ingredient in the possible causes. With the Tea Party "movement" and Joe Wilson's outburst, it is like I said earlier in September in a comment on Andrew Durkin's Jazz: The Music of Unemployment, "Until the Obamaphobes have some kind of 'intervention-like' revelation and come to question what they hear and believe on their own (and for many, certainly not all, to own up to how much race has to do with it all), they will continue down the road believing more and more illogical and specious arguments." And should add, possibly act on those arguments. As I see it now, in the climate of today's American new reality maybe the unspoken and unlikely now seems quite utterable and probable. So Vijay's postulate, to me, seems worth considering and exploring. Could "I don't like jazz" be a some kind of coded phrase representing some kind of bias, like the "I just don't like him" or "there is something about him I don't like" answers that some voters gave about Obama during the primaries? I don't want to get into any detailed, point-by-point Glenn Beck Da Vinci Code-like analysis of what is behind the words, for no one can know for sure except the person. Maybe more people do feel like they just don't understand it or are not part of the club, as Nancy said in the comments to the Twenty Dollar post ("I have to say that the reason jazz isn’t cool is because the jazz nerds have effectively shut the rest of us out of it. The way jazz fans fawn over and talk about jazz makes it unwelcome to any casual fan") but I can see that unconscious bias could also be there too. Because the people in the majority often do not see (or can even imagine) that some of biases are systemic and deeply ingrained. No matter how sophisticated, urbane, and fancied suited Wynton Marsalis and the J@LC crowd are, to some in middle and rural America (and yes, even in cities) they are no different than the baggy jeaned, white t-shirted "urban" youth seen hanging out on street corners. Where does something like that come from? It is certainly deep rooted. It's much like a thought experiment I heard about years ago: if you were a two dimensional being, you could never really see or understand the third dimension-much like we can't really "see" or wrap our brains around a fourth dimension. Oh sure, you could hint at it and speculate on it, but to really know it and see it. No. So to some people, believing the possibility that there is bias and prejudges in people (or that those "others" are like you), is like trying to see that fourth dimension. Often, inconceivable! I'm more inclined to see these issues with jazz, though, as one of economics and class, rather than race. And it certainly has to do with where the power (and hence the money) is. While today much of urban or black and Latino culture and music is fairly mainstream, the power or control in what people see, hear, and for the most part do, is not in the hands of minorities. A small group of tastemakers and insiders lets us know what is cool by what is covered, advertised, or showed. How many minorities are part of this group? Not many. Why? I tend to agree with Vijay in an earlier comment in the same Twenty Dollar post, that if you threw more money and cultural influence behind jazz or, I believe, at least had more minorities in positions of control you would see more brown, black, and yellow faces in the mainstream, which hopefully would lead to a rise in jazz coverage and thereby more people identifying with jazz, and those that make it, and feeling part of the fraternity. Where is the modern day Johnny Carson, who back in the day at the Tonight Show helped to give millions of non-fans a least a little exposure to hardcore jazzers such as Freddie Hubbard, Dizzy, MJQ, Miles, Ella, Sarah Vaughn by booking them to perform and interviewing them? what would happen if Oprah decided to do a Music Club, like her book club and feature people like Robert Glasper, Maria Schneider, Gretchen Parlato or Vijay (or even some contemporary classical types)? what if Jay Leno did something similar? or if there was some icon like Bono or some other younger adventurous, hip and cool artist/personality/star that could host a new web or TV program featuring different strands of jazz and other creative musicians from other genres, like David Sanborn did in the late 80s with Sunday Night? Certainly, just throwing money at the jazz exposure problem is not a viable solution because no amount of money will help if people just don't like or want to hear the product or producer (Mitt Romney, I'm talking about you) or the problem is too complicated for simple solutions (urban education and the so called achievement gap). Money can help, but it won't solve the jazz (and classical) cultural relevance gap by itself. For the most part, people like what they already know, they live and associate (mostly) with people they already know or think they know because of similar backgrounds, and they are reluctant to break through that inertia of complacency. Add to that, if the makers don't allow the humanness to come through the music ("too cool for school" attitude) or help to find ways to make connections with the listeners they hope to have, then we deserve the cultural hinterlands. If you didn't grow up with jazz/new classical/whatever art music genre or enthusiastically guided to the music by someone you know and trust or have the openness to come to it on your own, how will you know of the beauty, excitement, mystery, fun, joy, sexiness that can be in the music if we don't help others see it? POSTED BY NUMINOUS AT 11:31 PM |

The NuminosumTo all things that create a sense of wonder and beauty that inspires and enlightens. Categories

All

|

Thanks and credit to all the original photos on this website to: David Andrako, Concrete Temple Theatre, Marcy Begian, Mark Elzey, Ed Lefkowicz, Donald Martinez, Kimberly McCollum, Geoff Ogle, Joseph C. Phillips Jr., Daniel Wolf-courtesy of Roulette, Andrew Robertson, Viscena Photography, Jennifer Kang, Carolyn Wolf, Mark Elzey, Karen Wise, Numinosito. The Numinous Changing Same album design artwork by DM Stith. The Numinous The Grey Land album design and artwork by Brock Lefferts. Contact for photo credit and information on specific images.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed